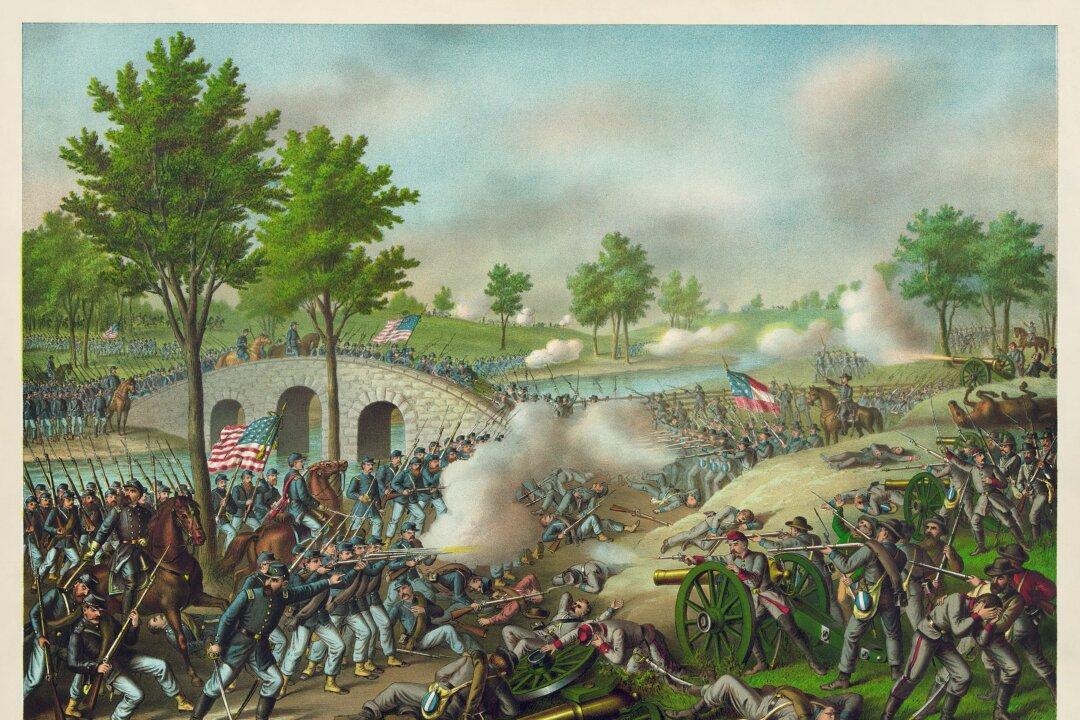

President Abraham Lincoln had a great deal on his mind in the summer of 1862. The Civil War dragged on, and the very fate of the nation hung in the balance. As he considered his responsibilities and authority as president, his resolve for a new measure grew.

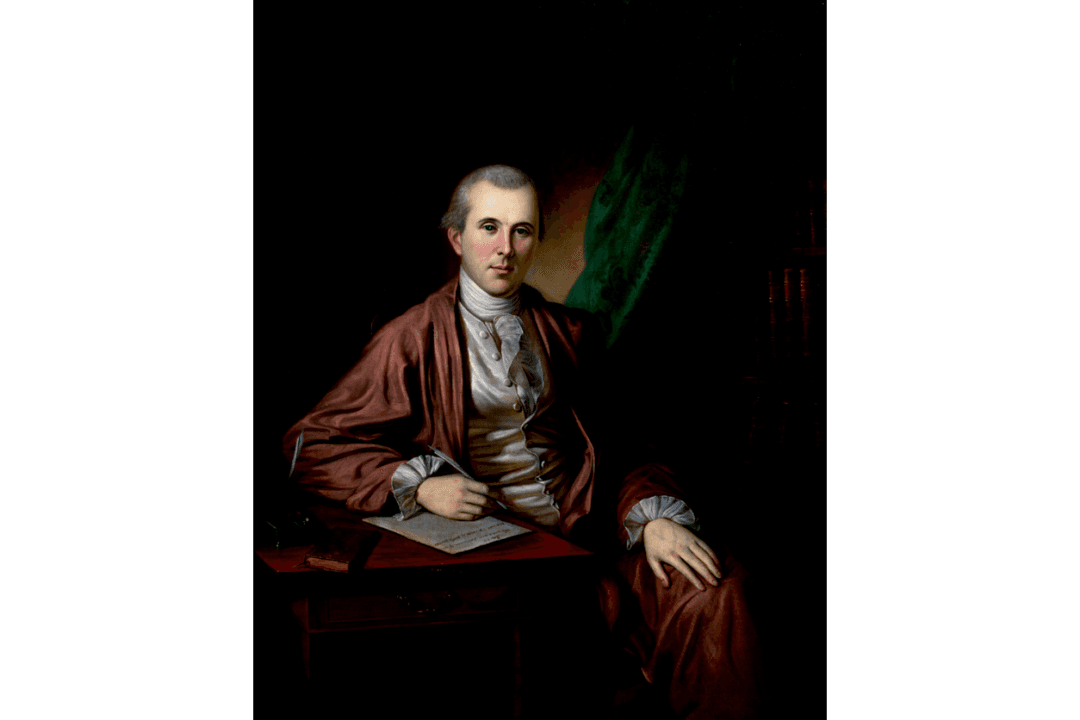

He invited Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Secretary of State William Seward to accompany him one day in July. As his carriage rolled toward its destination, for the first time Lincoln spoke of a proclamation—a document that would change the course of American history.