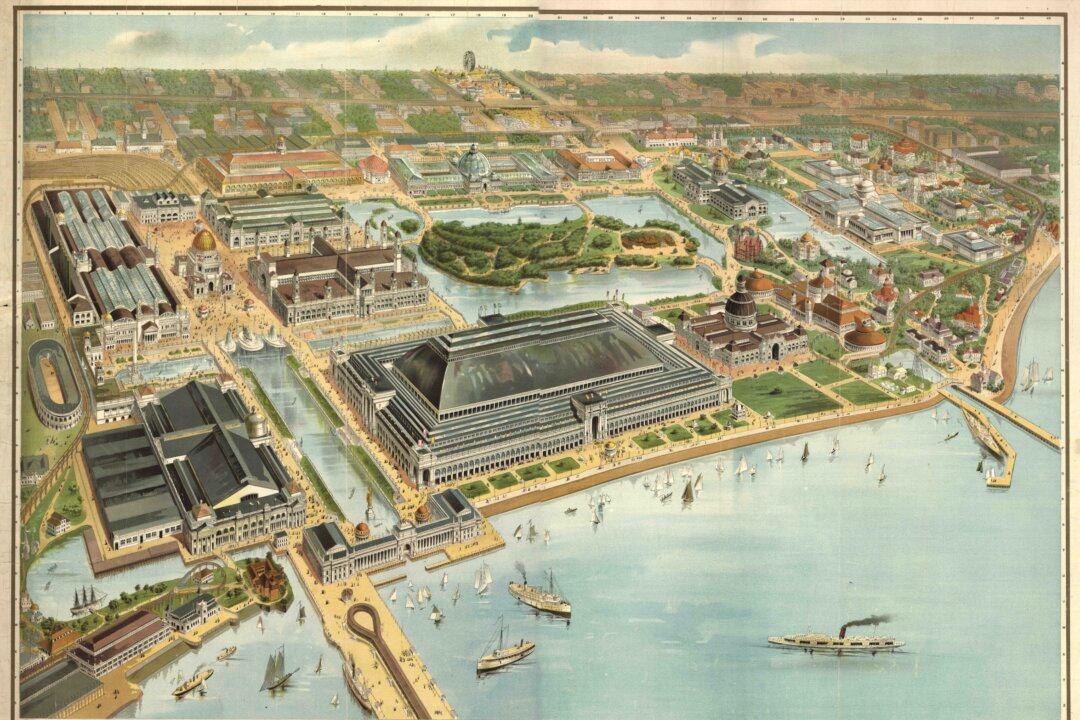

As the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition approached, architect Daniel Burnham grew increasingly concerned. The exhibition typically featured amazing scientific innovations and cultural experiences, and the 1893 exhibition had the unenviable position of following the spectacular 1889 exhibition in Paris, which saw the unveiling of the Eiffel Tower. Chicago received the honor of hosting the fair, but when it came to a crowning achievement like Eiffel’s tower, Burnham couldn’t find the right idea. Then, one day, engineer George Ferris approached him with an ambitious plan to amaze the masses: the Ferris wheel.

The Idea

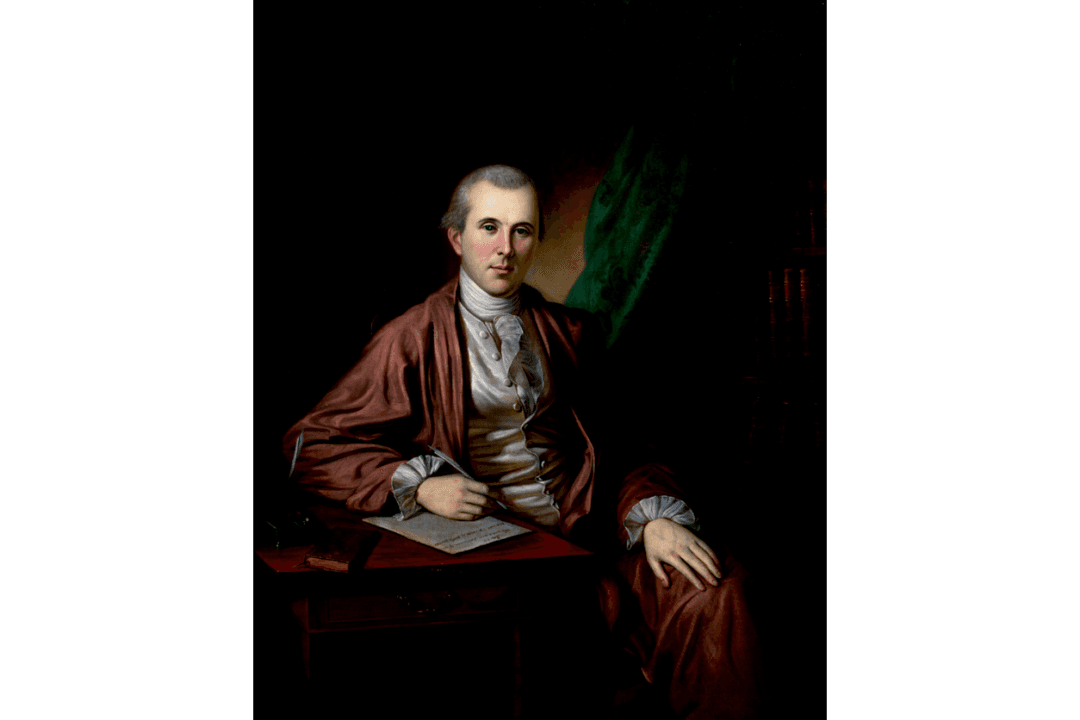

George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. was born on February 14, 1859, in Illinois. He grew up in Nevada and eventually received his engineering degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He embarked on a career as an engineer, eventually founding his own firm and building many large, ambitious structures. However, Ferris had no way of knowing that the bridges he was constructing would shrink in comparison to the project that would bring him fame beyond his wildest dreams.When Ferris heard about the structure Burnham and the others were seeking, he immediately came up with a plan and submitted it to the committee. Ferris imagined two giant, rotating wheels parallel to one another that lifted large cars of people into the air. These types of wheels had existed for years, but Ferris’s plan called for a much larger wheel than had ever been built.