One day in July 1893, James Cornish’s life changed forever. His trip to the bar that night turned into a brawl. Another man stabbed Cornish in the chest, and immediately he was rushed to the hospital. He stayed in the hospital overnight, continuing to worsen. By the morning, Dr. Daniel Hale Williams knew he had no choice. Cornish was in shock. This patient’s only chance was a risky surgery that simply didn’t happen at the time. Williams decided to open Cornish’s chest and try to repair the damage done to his heart. Thankfully for Cornish, he was in the hands of an incredibly skilled surgeon.

The Education of a Surgeon

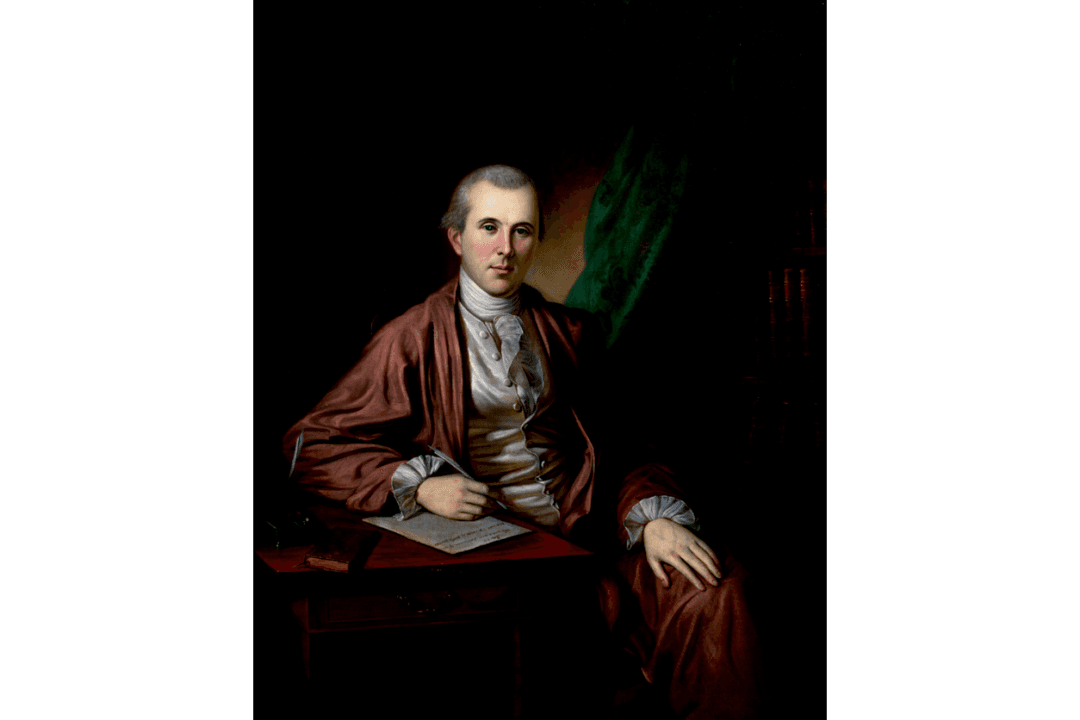

Daniel Hale Williams was born on January 18, 1856, in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania. Williams’s family lived well until his father became sick and died. With too many children to take care of alone, Williams’s mother sent him to Maryland to apprentice as a shoemaker. He soon left Maryland out of loneliness and found a variety of work over the ensuing years, from jobs on boats to cutting hair. However, he finally completed his high school education in 1877. Williams was unsure of where life would take him next, for though he was bright, he had yet to land on a profession. That all changed when he apprenticed for the well-known surgeon Henry Palmer.After studying under Palmer for a couple of years, Williams entered medical school. His university options were limited because he was African American, but he was accepted to Chicago Medical College (which would later become Northwestern University). Williams graduated from medical school a few years later and spent a year as an intern at Mercy Hospital in Chicago. Soon, he completed his internship and opened a practice of his own on the South Side. Williams taught anatomy for a few years at his alma mater while running his practice. As his reputation as a surgeon grew, so did his responsibilities. In 1889, he was appointed to the State Board of Health.