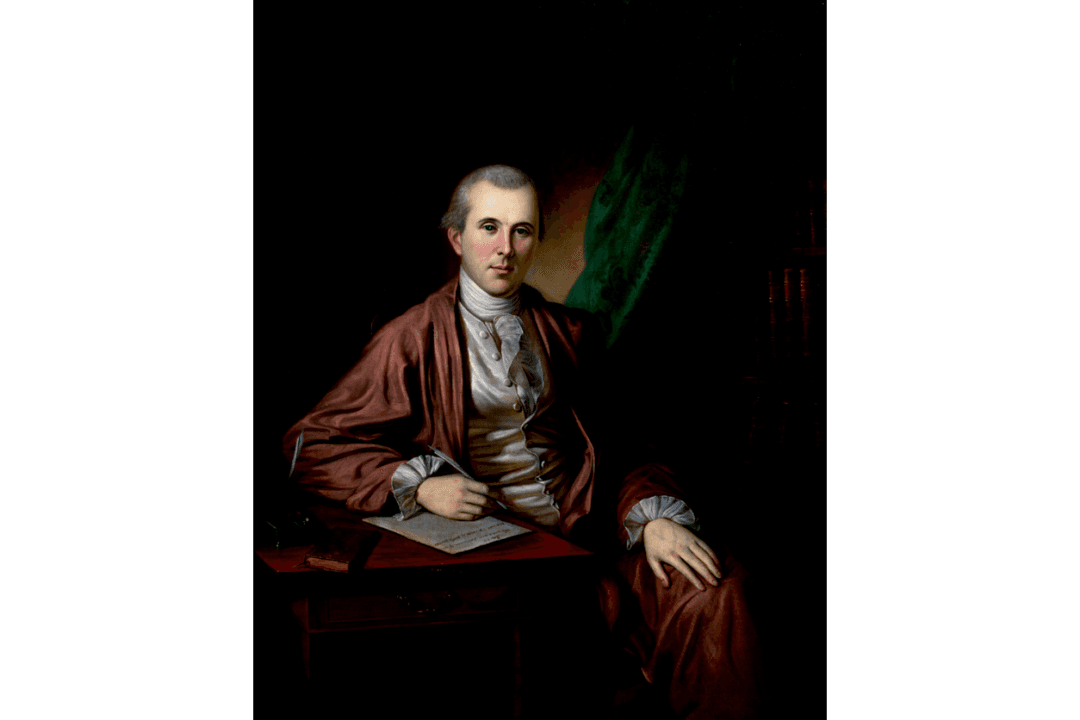

Many Founding Fathers were statesmen, soldiers, and lawyers, yet some came from more diverse walks of life. Benjamin Rush, a medical doctor, is best known as a Founding Father, but one of his life’s greatest endeavors was his work on mental health. Rush wanted to change the public perception surrounding mental health.

“Herewith you will receive a copy of my medical Inquiries and Observations upon the diseases of the mind,” Rush wrote to John Adams on Nov. 4, 1812. “I shall wait with solitude to receive your Opinion of them. They are in general accommodated to the ‘common science’ of Gentlemen of all professions as well as medicine. The Subjects of them have hitherto been inveloped in mystery. I have endeavored to bring them down to the level of all the other diseases of the human body, & to show that the mind and body are moved by the same causes and Subject to the same laws.”