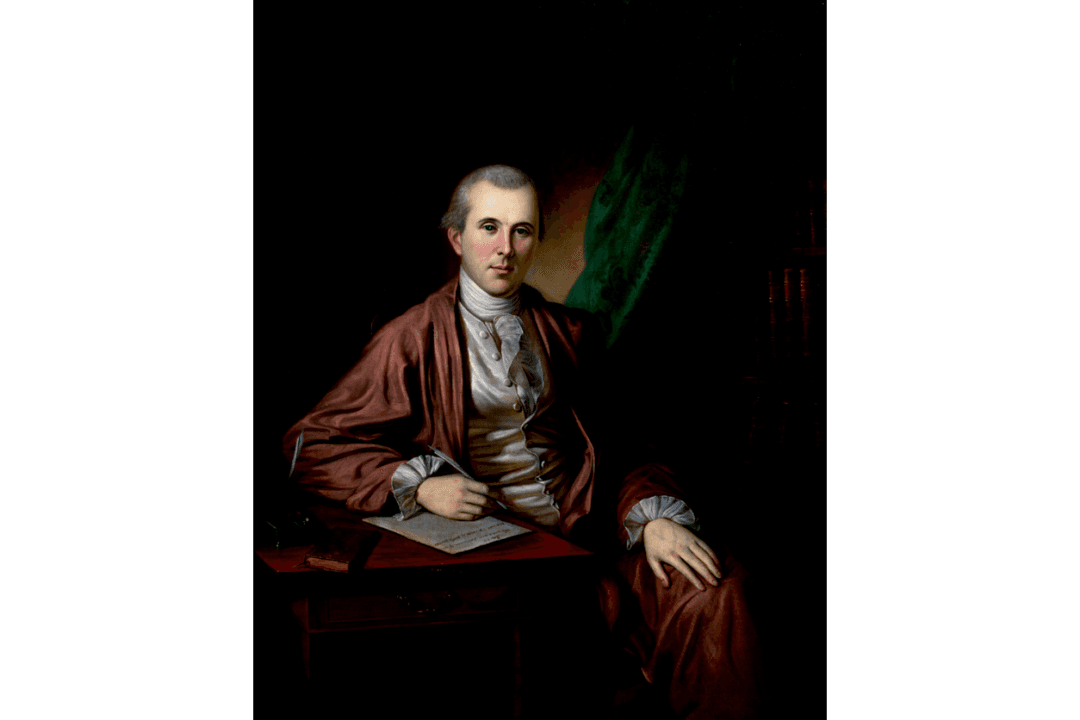

“There was not a good Bookseller’s Shop in any of the Colonies to the Southward of Boston. In New York and Philadelphia the Printers were indeed Stationers, they sold only Paper, etc., Almanacks, Ballads, and a few common School Books. Those who lov’d Reading were oblig’d to send for their Books from England,” Benjamin Franklin wrote, recalling the state of reading materials in Philadelphia prior to 1731. Franklin, an avid reader, pondered how to right this wrong and produce access to enough expensive reading materials to satisfy himself and his friends without bankrupting them all in the process.

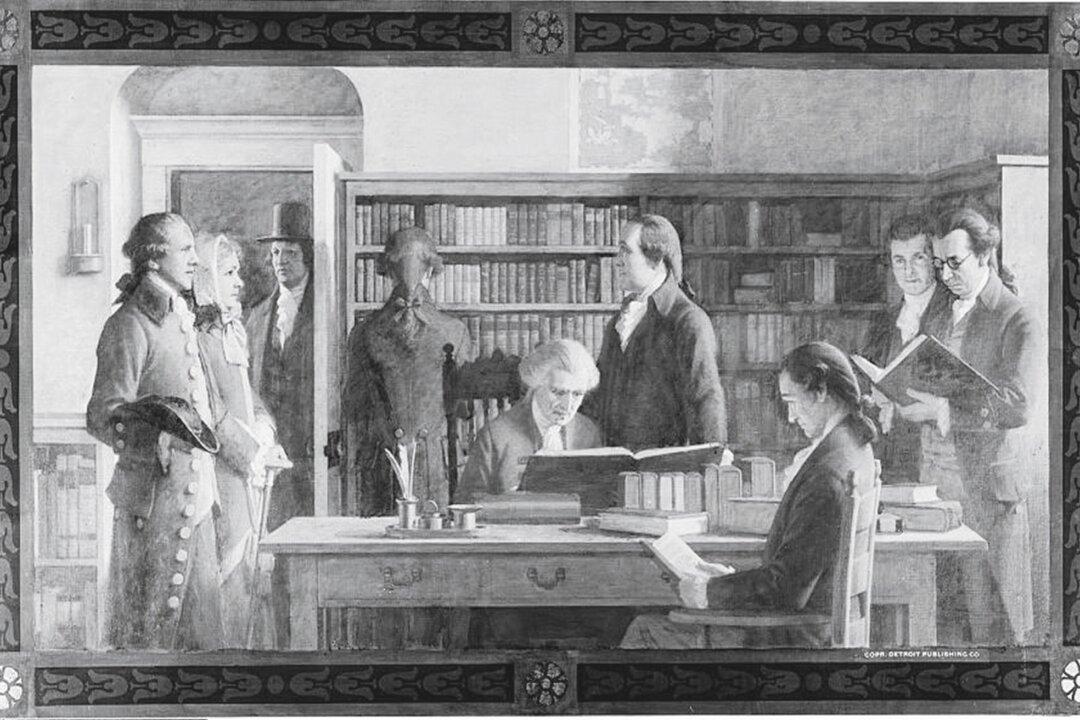

His first solution called for the members of the Junto, a discussion group in which Franklin was a member, to pool their personal libraries and borrow each other’s materials. They collected the books in a rented room and used them as references during their discussions. Unfortunately, the experiment didn’t last long. Some of the books were damaged, while others went missing entirely. After about a year, the respective members took their books home. Though this experiment was a failure, Franklin wasn’t deterred. He dreamed up an even more ambitious idea.