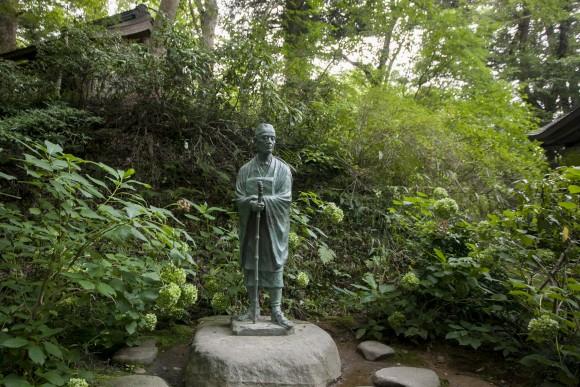

Climbing 2,446 steps requires endurance. As I made my way up, looking for the renderings of Buddha said to be etched into the stone steps, I began to ponder why Basho (1644–1694), the 17th-century Japanese master of haiku, had journeyed all the way here on foot, from the outskirts of Tokyo. I was on Mount Haguro, one of the three sacred mountains of Dewa in northern Japan.

This was one of the stops on a 10-day walking tour organized by Walk Japan, a tour company that specializes in exploring off-the-beaten-path areas of the country, mostly on foot. Led by an American guide who had spent more than a decade living in Japan, our group (one American, two Brits, an Australian, and a Finnish couple) re-traced Basho’s 1689 journey—the final trip of his life—through the northern region of Honshu, the largest island in Japan.

[gallery size=“medium” ids=“2226450,2226453,2226452”]

We had as our guiding itinerary Basho’s account “The Narrow Road to the Deep North.” The poet set out from his hut in Edo (today’s Tokyo), traveling up the east coast of Honshu, then descending along the west coast to end at Ogaki. We would trace a similar route, but finish in Japan’s former capital, Kyoto.

Basho was prepared to never return from this treacherous voyage. Why would he want to go through such travails?

By the time I reached the top, with a towering orange torii gate in sight, I had begun to understand. Bearing hardship is good; it makes the reward that much sweeter. When you make the effort to travel somewhere on your own two feet, the beauty of what you see at the end destination is magnified.