Finding Hope in the Depths of War (Photos)

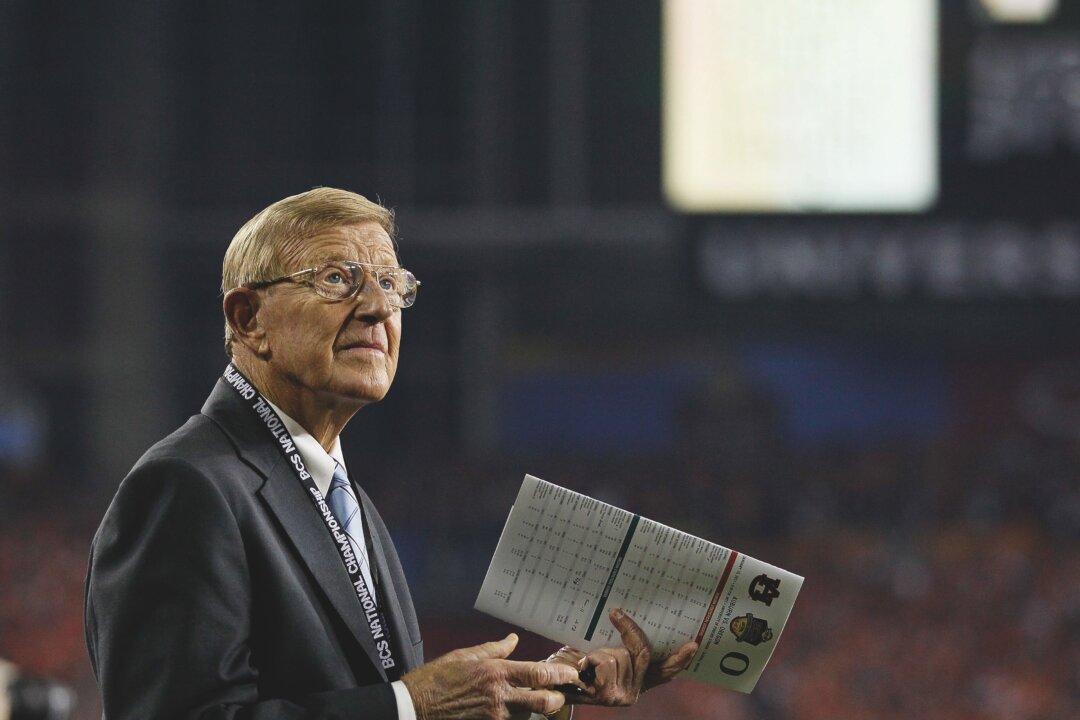

At a cozy Italian restaurant, renowned photographer Tony Vaccaro was flipping through the pages of his book, “Entering Germany: Photographs 1944—1949,” as Mozart’s music was playing lightly in the background.

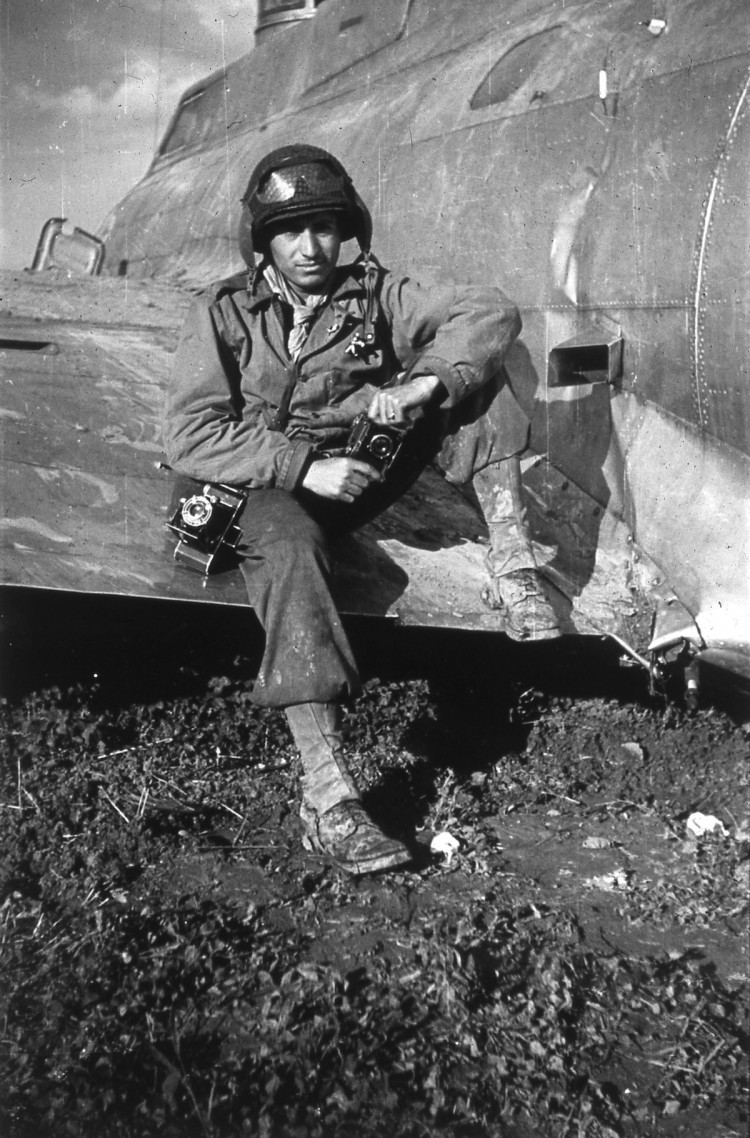

YOUNG PRIVATE: In 1944, Tony Vaccaro was with the 83rd Infantry Division of the U.S. Army on the Western front. He called his camera, a 35mm Argus C3, 'black brick.' Courtesy of Tony Vaccaro

|Updated:

Annie Wu joined the full-time staff at the Epoch Times in July 2014. That year, she won a first-place award from the New York Press Association for best spot news coverage. She is a graduate of Barnard College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

Author’s Selected Articles