Boom! Canon fire echoed across the state of New York on October 26, 1825. Men listened carefully at their posts, firing their canon once they heard the distant sound of another. This relay stretched from Buffalo to Manhattan, where the final canon proclaimed that the Seneca Chief had departed Buffalo and was making its way to the coast. The waterway on which it traveled had not even existed a decade before, but now this boat would sail from the eastern shore of Lake Erie to the Atlantic Ocean. It was the first to travel the entire length of the Erie Canal.

The Impossible Feat

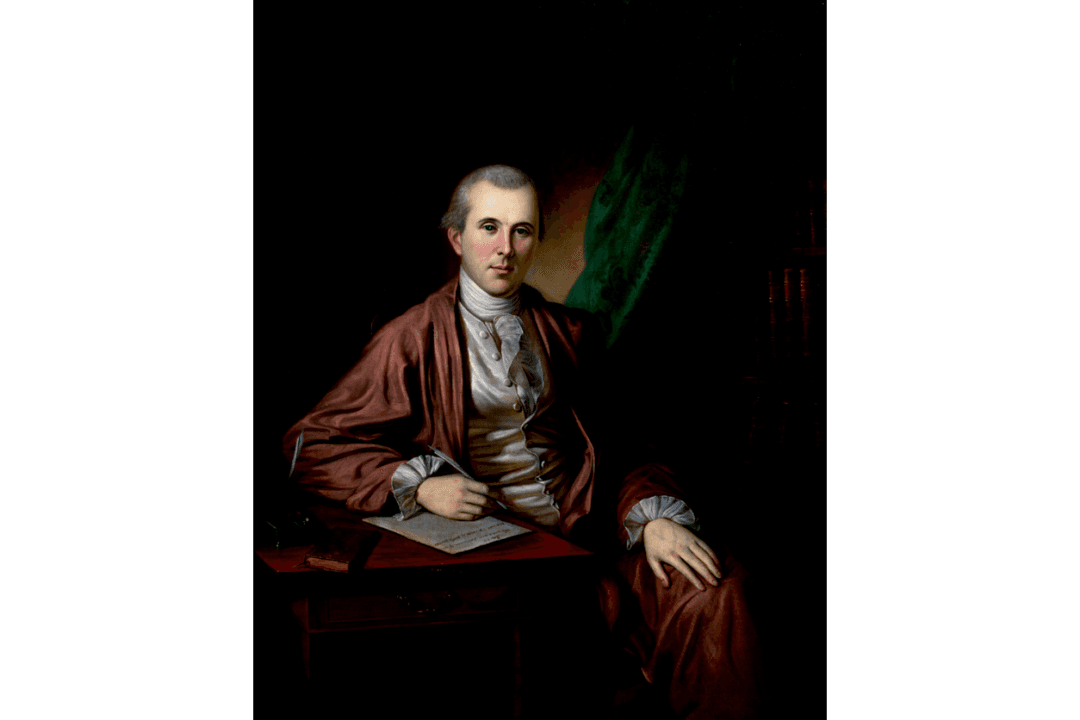

As the 19th century dawned and pioneers journeyed west into the Great Lakes region, some advocated for a safer, faster, more reliable form of transportation from the resource-rich land to the coast. As early as 1800, the founding father Gouverneur Morris advocated for a great canal. He wrote:Does it not seem like magic? One-tenth of the expense born by Britain in the last campaign would enable ships to sail from London through Hudson’s river into Lake Erie. Hundreds of ships will in no distant period bound the billows of those inland seas. … We only crawl about on the outer shell of our country. The interior excels the part we inhabit in soil, in climate, in everything. The proudest empire in Europe is but a bauble compared to what America will be and must be, in the course of two centuries, perhaps of one.However, some thought that such a large canal would be impossible to complete. “Talk of making a canal 350 miles through wilderness is little short of madness,” Thomas Jefferson declared in 1809.

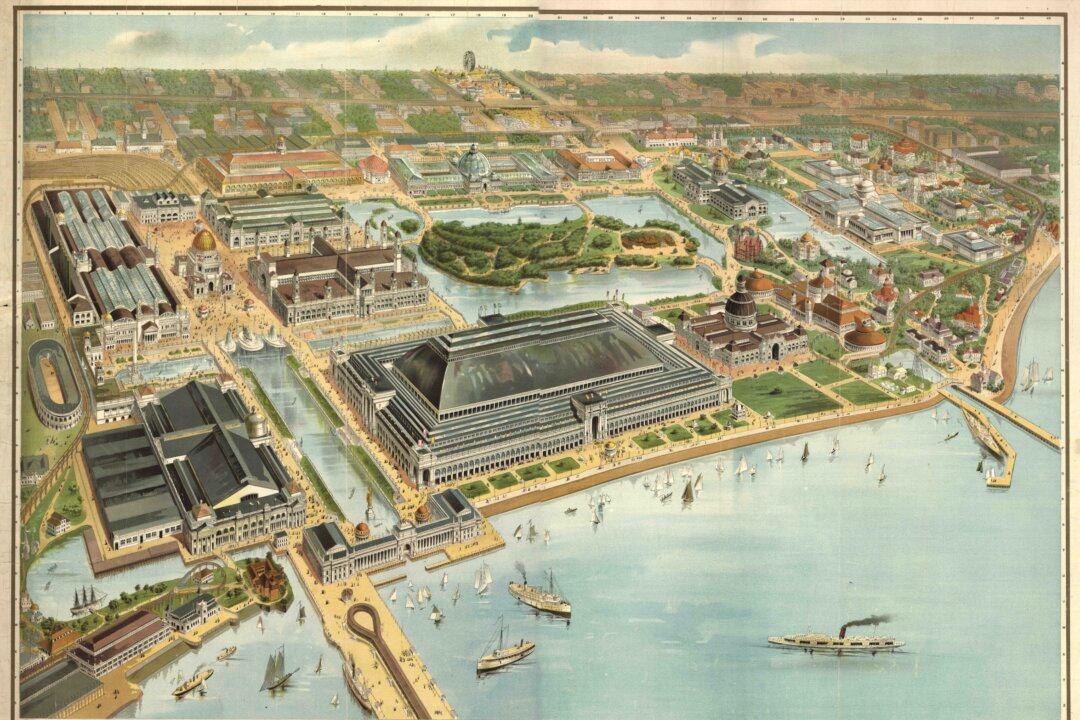

A bird’s-eye view of the Erie Canal and Railroad connecting to Cayuga Lake, the longest of the Finger Lakes. Matt Champlin/Moment/Getty Images