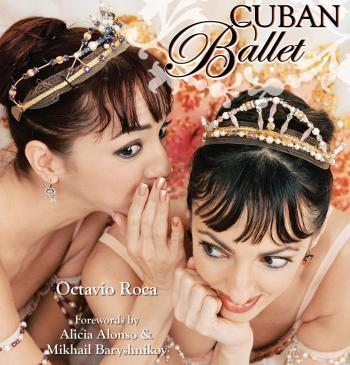

“The story of Cuban ballet is funny—it’s like a novel that just happens to be true,” Octavio Roca said when asked about his relationship to Alicia Alonso, the great prima ballerina and pioneer of the Cuban school of ballet. Roca, a former dance critic for The Washington Post and The San Francisco Chronicle and now a philosophy professor, revealed that writing his new book, Cuban Ballet was in many ways like reflecting upon his own life journey.

Having grown up watching his ballerina mother dance in the Ballet de Pro-Arte Musical in Cuba, Roca witnessed the flourishing Cuban ballet movement at its inception. In the first ballet he ever watched, Giselle, Alonso was Giselle (the peasant girl) and his mother one of the Wilis (evil spirits). Thereafter, Roca covered Cuban ballet throughout his critical career, writing about Alonso’s Ballet Nacional de Cuba and the waves of Cuban dancers (many of whom received their training at Alonso’s company) defecting to dance companies abroad. Thus, Roca has known Alonso his whole life, both of them proud Cubans and avid lovers of dance.

Equipped with his extensive knowledge of the arts, Roca chronicles the history of Cuban ballet through vivid anecdotes and scores of gorgeous photos, written with an honest and yet impassioned sensibility to dance and its most inspiring figures.

Cuban Ballet—A School of Its Own

Today, the growing number of Cuban dancers in exile, especially those who defected to America, has profoundly influenced American and world dance, much like how the Russians did in the ‘70s and ’80s when they left the Soviet Union amid its disintegration.

But the dance world did not immediately recognize Cuban ballet as a distinctive school capable of revolutionizing the art. “A lot of [critics], especially political critics, assume that because Cuba was under the influence of the Soviets for so very long, that the ballet must be the same. Actually, it’s not. It’s a very different tradition …The important thing is that they have a very New World look,” Roca explained.

When Alicia Alonso established her own Ballet Alicia Alonso (which later became Ballet Nacional de Cuba) in 1948, the company already had its own training and style of dancing attached to it. Roca took note of the differences between the Russian and Cuban dancers’ movements: “For example, in terms of preparation, the way a dancer prepares for a step, the Russians are known for their time … there was a way of taking a deep breath before going into a step … Cubans are the opposite. Because they began working at the same time as George Balanchine started working in New York … and what they do is they hide the preparation completely, so their moves come out of nowhere. They’re very, very fast. They have the same articulation as the Russians do, which is very clean, but they have a faster way. In many ways, they’re even a step ahead of the beat. It’s a very different look.”