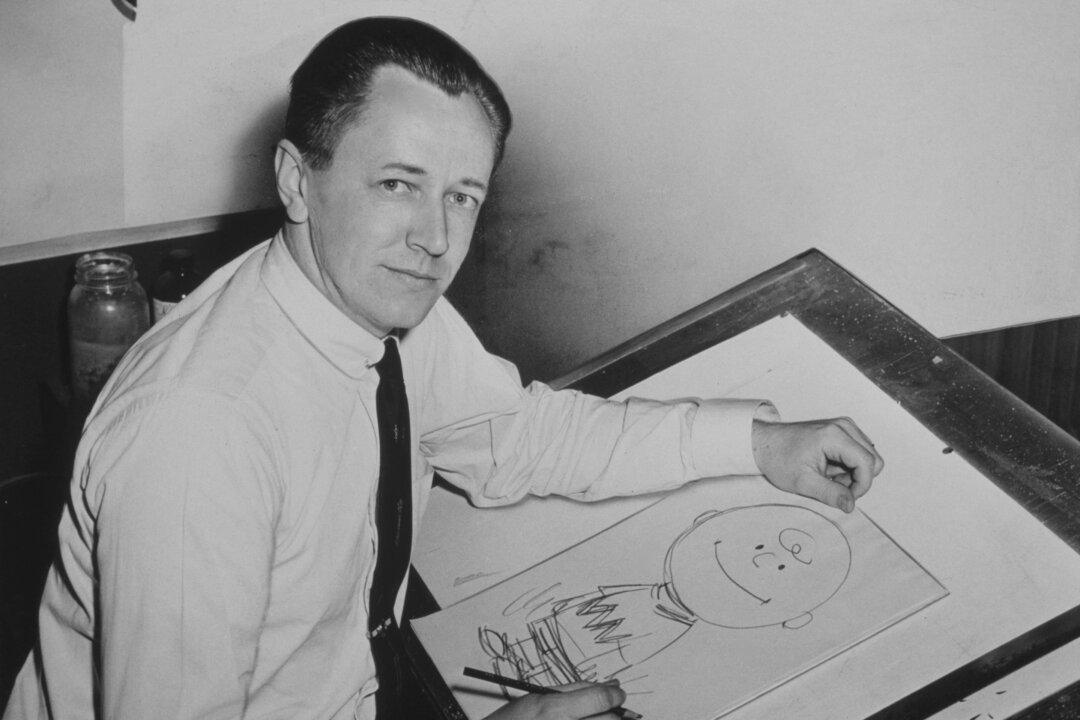

People today likely remember the “Peanuts” TV specials better than Charles Schulz’s comic strips. He wrote the script for “A Charlie Brown Christmas” himself, and as his Christian faith was very important to him, he made the climax of the program Linus reading from the Gospel of Luke. The special was an instant success, and many families still enjoy it every year. However, it was his comic strips that brought him fame.

“My dad was always a great comic strip reader, and he and I made sure that all four newspapers published in Minneapolis–St. Paul were brought home. I grew up with only one real career desire in life, and that was to someday draw my own comic strip,” Schulz, creator of the “Peanuts” comic strip, wrote in his autobiography. His comic strip entertained thousands of people for decades with the adventures of Charlie Brown, Snoopy, and their friends. However, his path to becoming a cartoonist was anything but easy.