We all love to see beautiful things. What would our lives be without beauty? Yet there’s always the chance that beauty adorns and accompanies harmful things. How do we discern when something is truly beautiful or when beauty merely masks the detrimental?

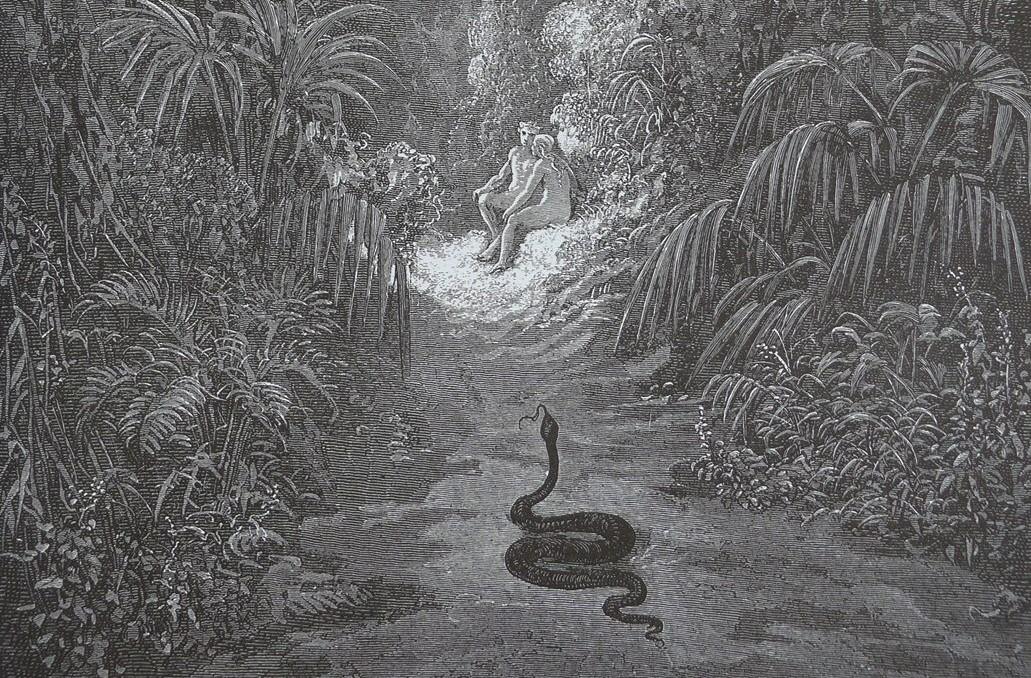

In this penultimate part of this series, we continue to extract wisdom from Milton’s interpretation of the biblical story of Adam and Eve. Previously, we left Satan as he turned into a serpent to find a way to hurt God through Adam and Eve. Adam and Eve were blissfully enjoying the Garden of Eden, unaware of Satan’s presence, although the Archangel Raphael has warned them about Satan.

The Union of Wisdom and Beauty

Upon waking, Adam and Eve wish to tend to God’s garden, to shape it and mold it into a beauty respectful of God, but there’s so much to tend to. Eve suggests that they split up, but Adam is concerned that Satan will have better success hurting them if they’re apart:But other doubt possesses me, lest harm Befall thee severed from me; for thou know’st What hath been warned us—what malicious foe, Envying our happiness, and of his own Despairing, seeks to work us woe and shame By sly assault and somewhere nigh at hand Watches, no doubt, with greedy hope to find His wish and best advantage, us asunder, Hopeless to circumvent us joined, where each To other speedy aid might lend at need. (Book IX, Lines 251–260)

Adam reveals an important aspect of the relationship between the masculine and feminine: They must work together and aid each other against evil’s onslaught. Milton also repeatedly refers to Adam’s wisdom and Eve’s beauty throughout his writings, suggesting that these two—wisdom and beauty—must work together as one if resistance to temptation and obedience to God are to be accomplished.