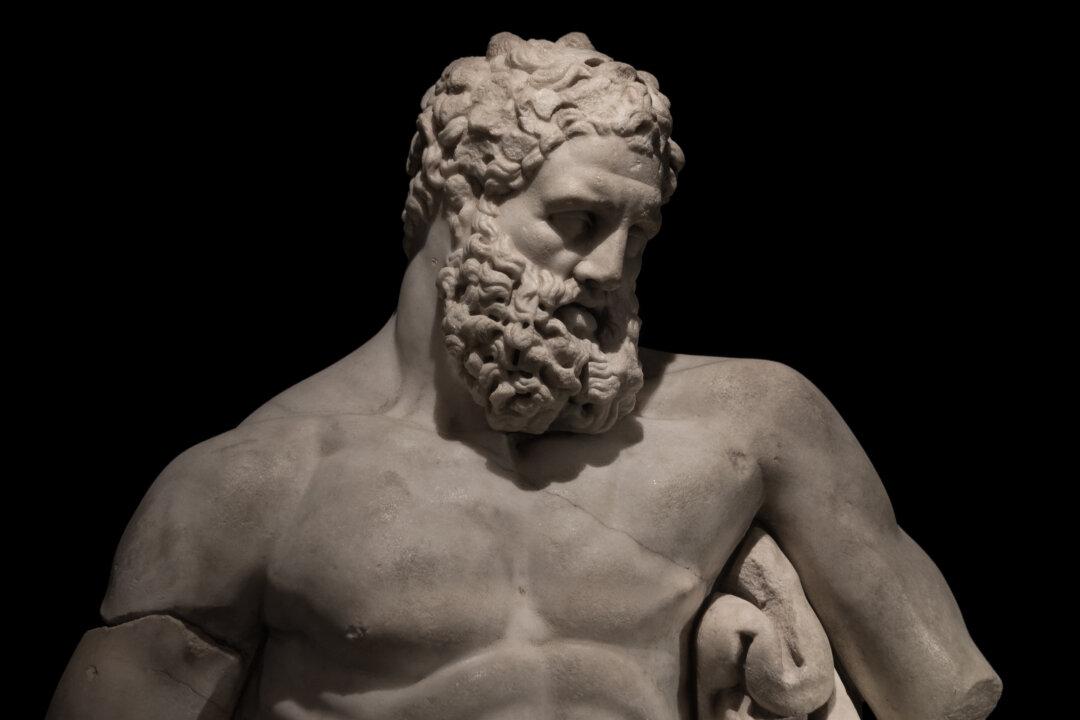

What makes someone truly great? How do certain people achieve great things? In order to answer this question, we have to consider what “greatness” means. Here, we are not considering those people or their contributions that are popular. These quickly fall out of favor.

Instead, greatness refers to those people and their contributions that transcend time and place.