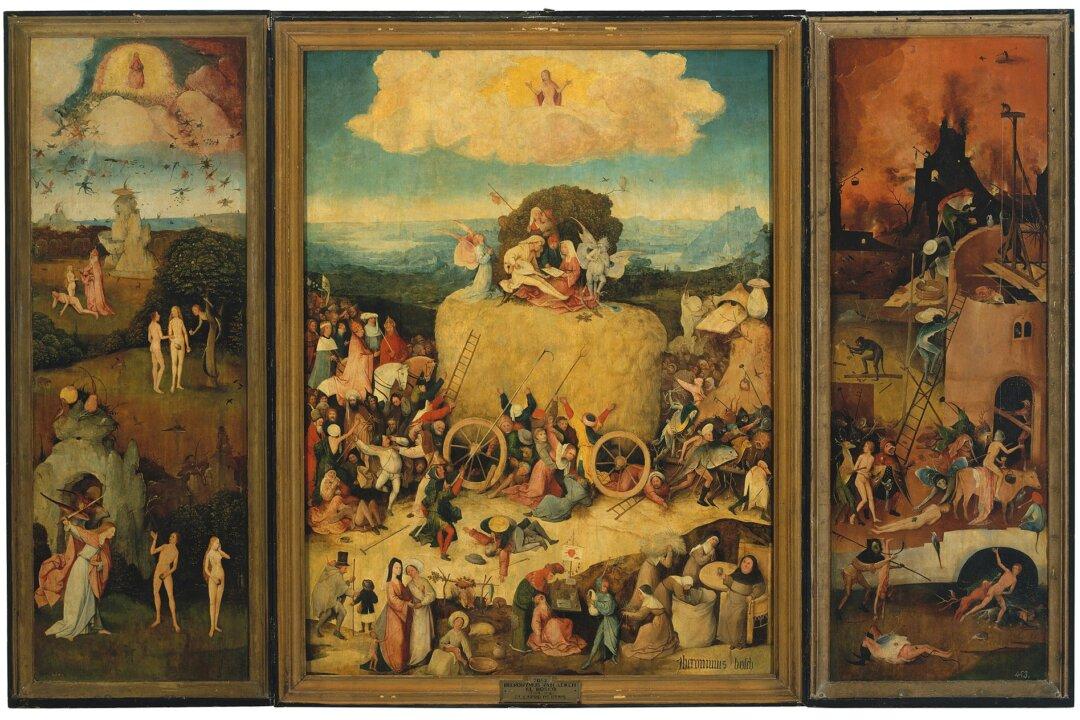

Have you ever worked really hard for something or wanted something badly only to care little for it after you have gotten it? Or have you wanted something really badly only to regret having it after you’ve gotten it? I have experienced both of these. Sometimes things seem great when seen from a distance; the grass always seems greener. But I’ve forgotten that grass is just grass. I believe Hieronymus Bosch is saying something similar with his painting “The Haywain.”

Bosch was a member of the religious confraternity “Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady,” which was dedicated to venerating the Mother of God, the Virgin Mary. Many of his paintings were made for the confraternity and display religious subject matter, but they often use strange and even disturbing imagery.