On July 17, 1717, London witnessed a spectacle like no other. Crowds gathered as 50 musicians set out to play Handel’s glorious “Water Music” on open boats along the River Thames for King George I and his royal boating party. Written especially for the occasion, the majestic collection of instrumental suites amazed the British public for its original setting and joyous music, reviving popular support during the king’s reign, and creating an enduring cultural legacy of classical music.

A Royal Show

King George I (1660–1727) wasn’t too popular at the beginning of his reign. In 1717, not long after his coronation, he faced political opposition from the public and even from his own family, as an opposing party formed to favor his son, the Prince of Wales. The king’s advisors suggested that he do something big to win over the people. That’s when the idea of throwing a lavish summer boating party on the Thames, with grand musical entertainment, came about. George I staged a royal show for his subjects that they did not soon forget. And who better to compose music for this occasion than George Frideric Handel, the king’s royal composer?

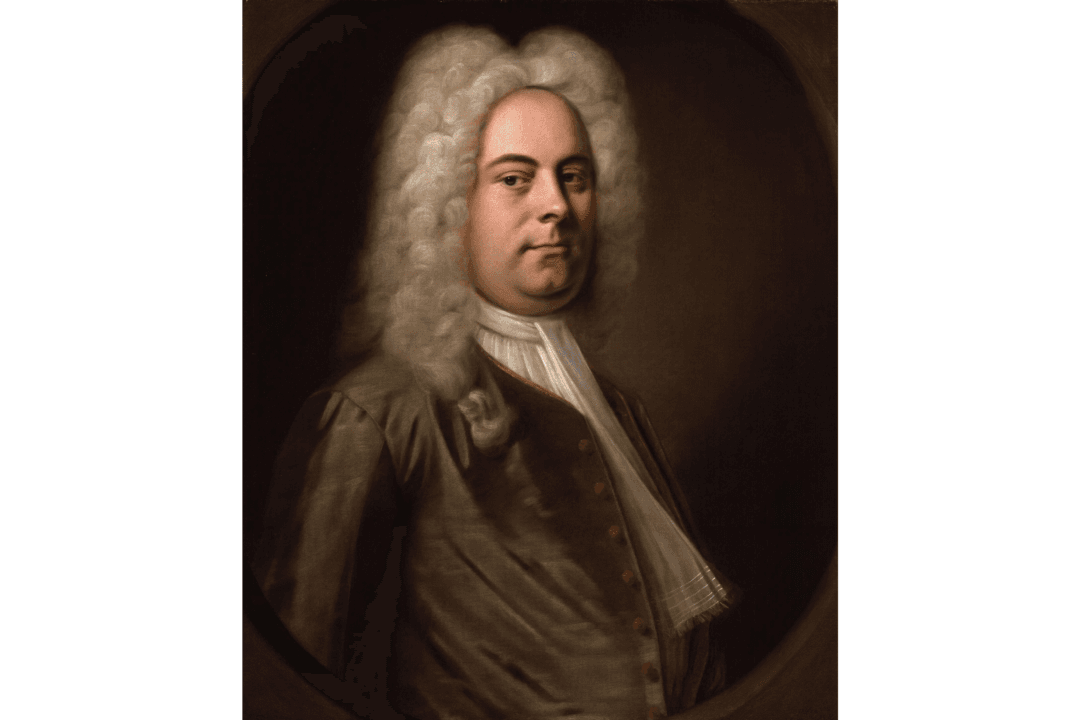

Handel (C) and King George I on the River Thames, July 17, 1717, by Edouard Hamman. Public Domain