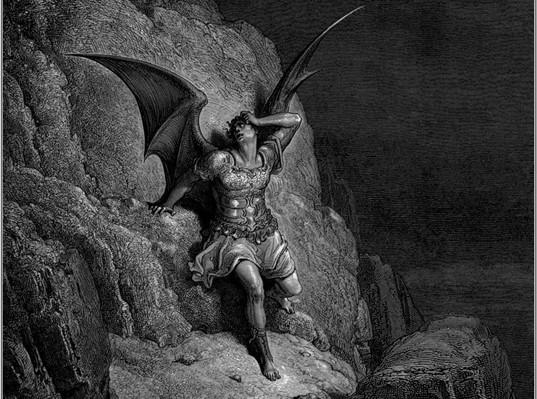

Throughout our series “Illustrious ideas and illustrations: The imagery of Gustav Doré,” we’ve had the opportunity to take a deep look at how the poet John Milton saw Satan. Satan, the father of Sin and Death, has been shown as synonymous with pride, vanity, deception, and revenge.

There’s still more to understand about Milton’s conception of Satan. Continuing from where we left off in the last article, Satan has just deceived the archangel Uriel in order to find out the location of Earth so he can attack God’s new creation: human beings.

Satan’s Inner Torment

After arriving on Earth and coming close to Eden, Satan is overwhelmed by fear and doubt. He confronts the truth about his relationship with God:“horror and doubt distract His troubled thoughts, and from the bottom stir The Hell within him, for within him Hell He brings, and round about him, nor from Hell One step no more than from himself can fly By change of place: now conscience wakes despair That slumbered, wakes the bitter memory Of what he was, what is, and what must be Worse …” (Book IV, Lines 18–26)

First, Milton tells us that hell is following Satan no matter where Satan goes. Despite passing his children, Sin and Death, to exit hell, Satan is still tormented by its presence. Hell is a state of being for Satan; it was not only the environment he was cast into but is also the characteristic of his conscience.