Let’s get these points out of the way up front.

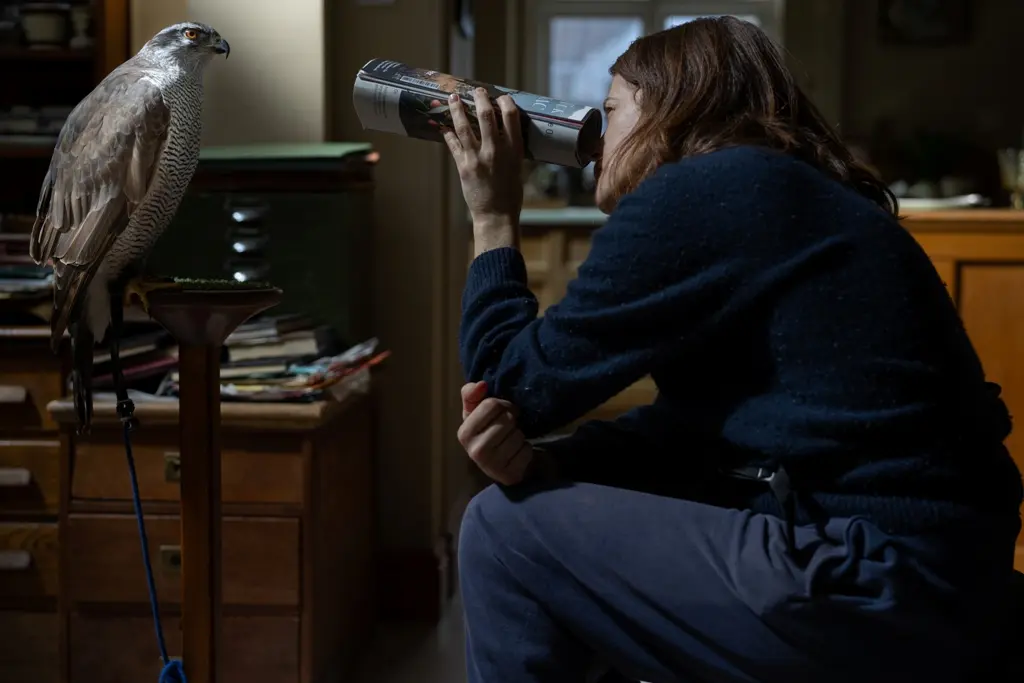

‘Sympathy for the Devil’: Cage at his Cagiest

Nothing is as it seems in this cat and mouse crime thriller

Originally from the nation's capital, Michael Clark has provided film content to over 30 print and online media outlets. He co-founded the Atlanta Film Critics Circle in 2017 and is a weekly contributor to the Shannon Burke Show on FloridaManRadio.com. Since 1995, Clark has written over 5,000 movie reviews and film-related articles. He favors dark comedy, thrillers, and documentaries.

Author’s Selected Articles