We all deal with hardship. Irrespective of race, class, or gender, we all suffer. Suffering is a fact of life. It is inevitable. How can we approach suffering with poise and grace? How can we use it to better understand ourselves? The stoicism of the Roman philosopher and statesman Seneca may provide some insight.

Seneca’s Life and Philosophy

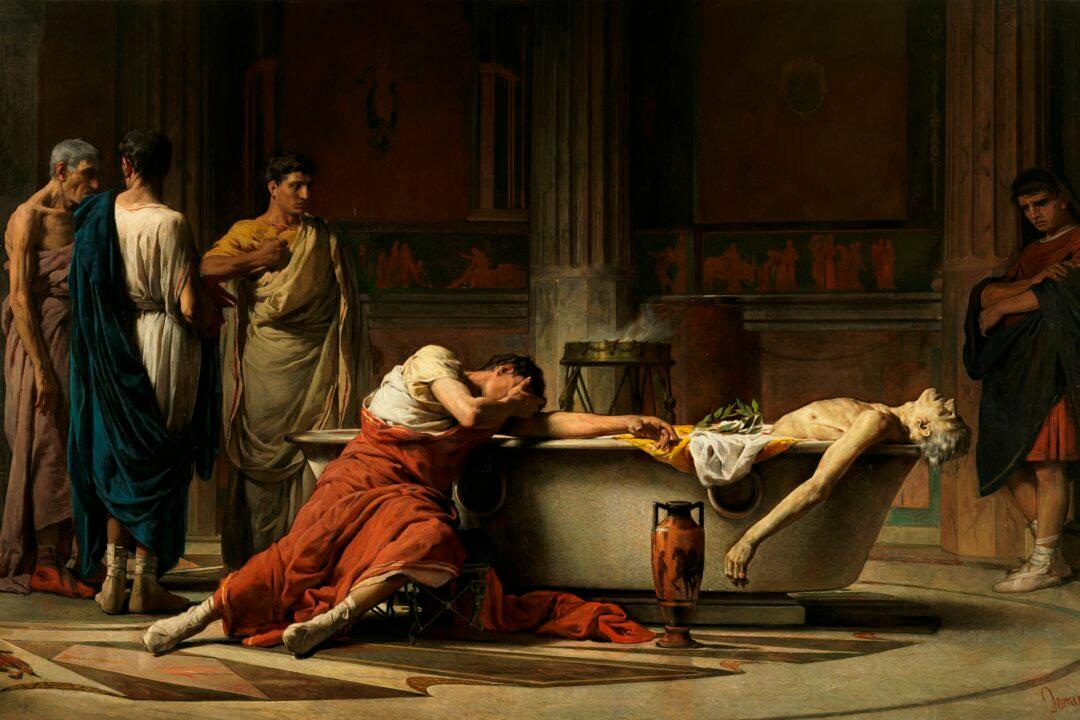

Seneca, born around the start of the first century, trained at a young age in rhetoric, literature, and stoic philosophy. Stoicism is a philosophy that focuses on virtuous behavior, control of the emotions, and the rational use of the mind.Seneca’s stoicism is grounded in the thought that destructive emotions such as anger and grief should be moderated and removed, that wealth should be used in accordance with virtue, that friendship and kindness are significant, and that hardship should be gracefully accepted instead of avoided. Seneca attempted to live according to these stoic principles whenever he faced hardship.