The poet W.H. Auden shunned detective stories because, he wrote, “Once I begin one, I cannot work or sleep till I have finished it.” Auden was not alone; 20th-century readers couldn’t get enough of them, and authors struggled to keep up. Erle Stanley Gardner published over 80 novels featuring his lawyer-sleuth Perry Mason, while Agatha Christie’s 66 mysteries made her the bestselling author of all time, after Shakespeare and the Bible.

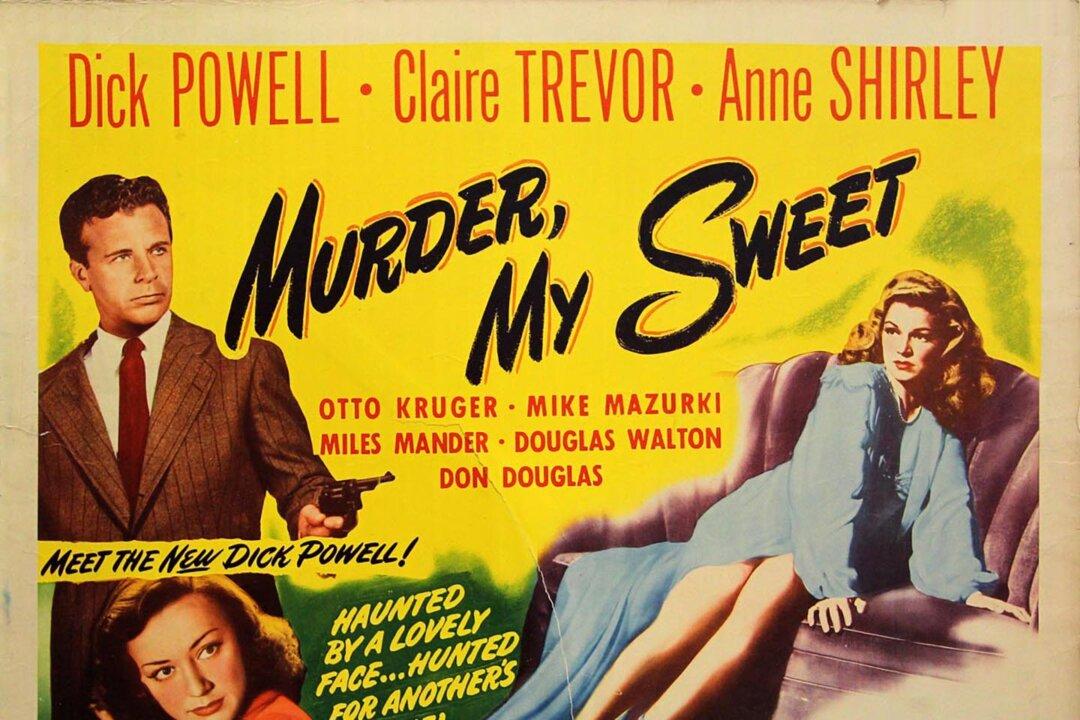

Christie’s posh British style—the suspects in the drawing room, the body in the shrubbery—inspired TV hits like “Columbo” and “Murder She Wrote,” and movies right up to the recent “Knives Out” (2019) and its upcoming sequel.