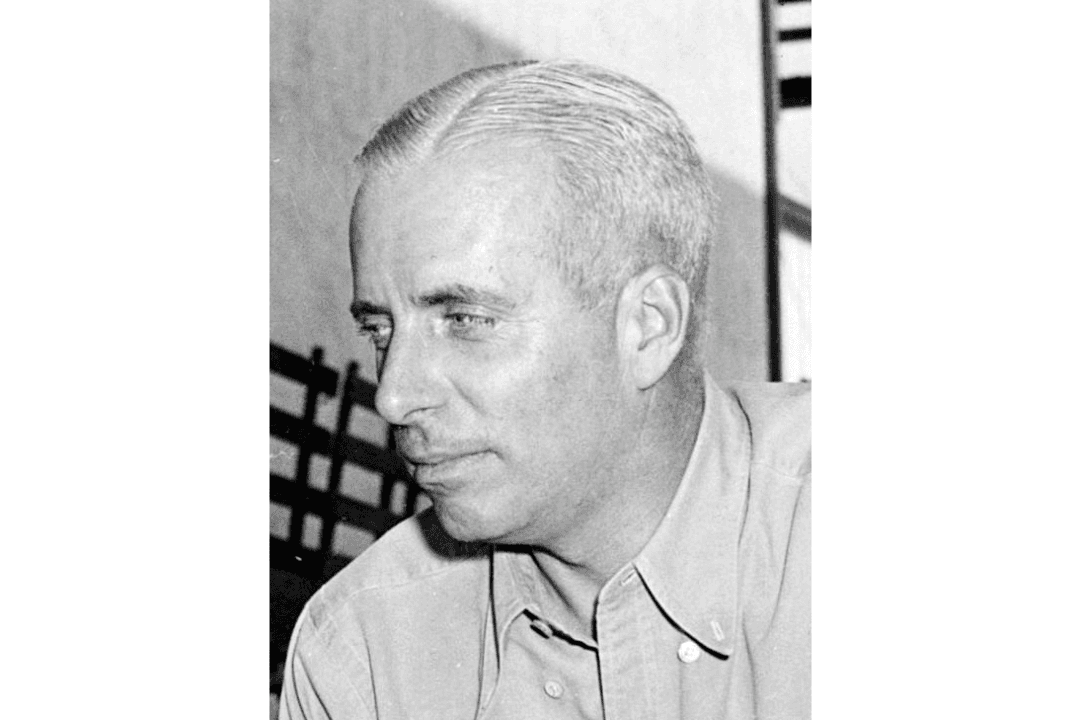

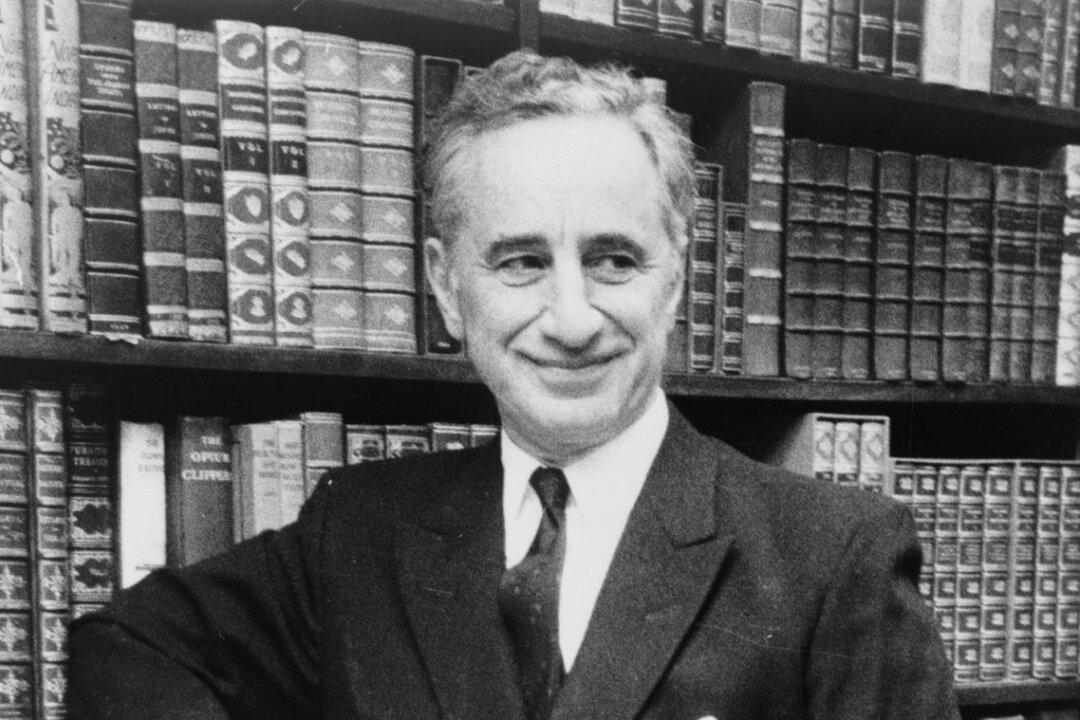

Hollywood’s Golden Age, roughly from 1915 to the early 1960s, produced many fine directors, but only a few became household names. John Ford made westerns—movie fans know—and Alfred Hitchcock was the master of suspense. If the great Howard Hawks is less well-known, it may be the fault of his versatility.

Unlike Ford and Hitchcock, Hawks made outstanding films in many genres: westerns, comedies, crime stories, science fiction, and even a hit musical. Stubbornly independent, he never hitched his wagon to a single studio. At various times he worked for all eight of the major ones.