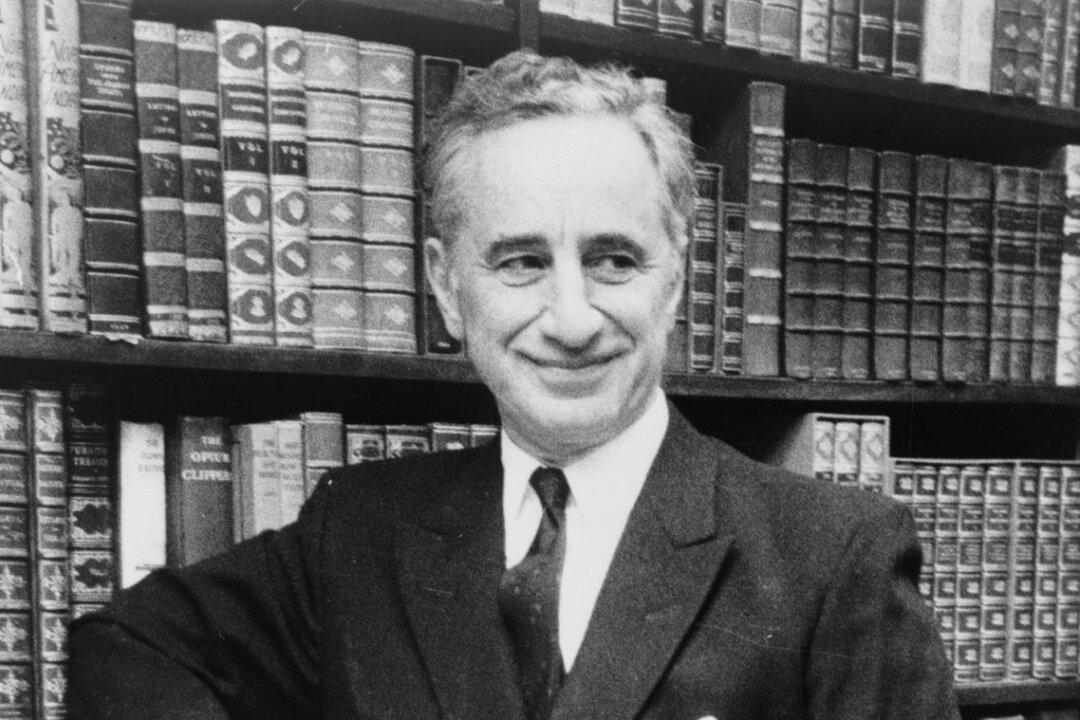

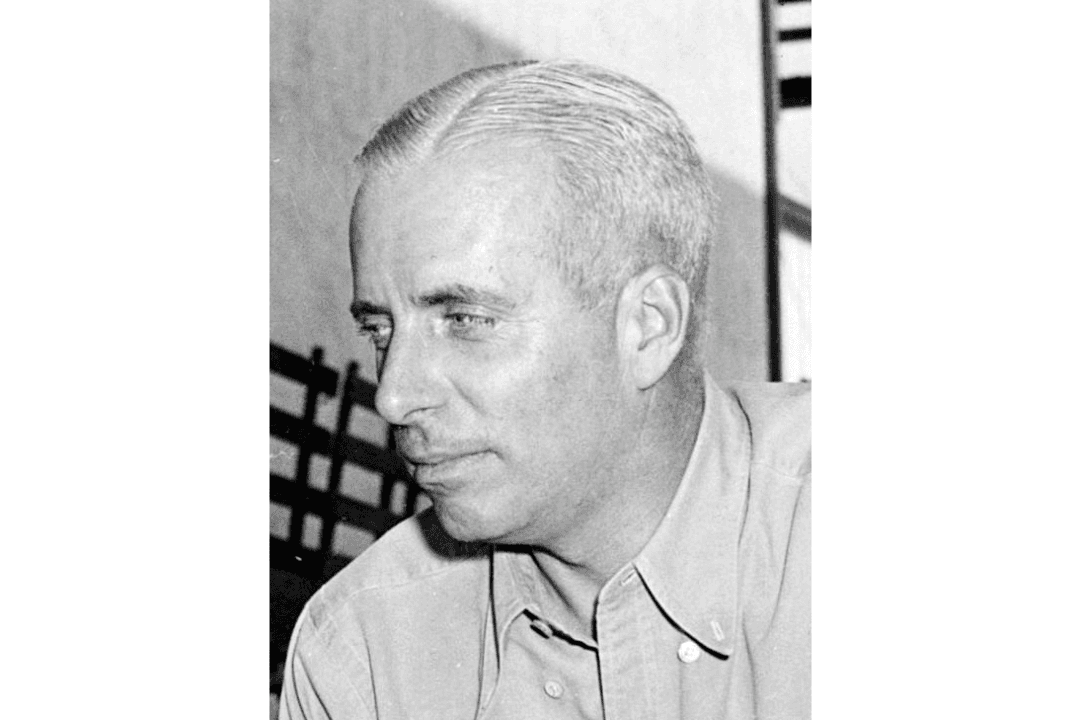

At the 1999 Academy Awards, “Shakespeare in Love” won seven statuettes and Elia Kazan, one of Hollywood’s greatest and most influential directors, received one for Lifetime Achievement.

This wasn’t your typical Oscars. Before the ceremony, nervous producers and scantily-clad starlets had to run the gauntlet between two groups of shouting protesters. Five hundred had gathered to denounce Kazan, carrying signs that read, “Don’t whitewash the blacklist!” and “Kazan is a rat!” A smaller group supported the director. Fights broke out. Police had to disperse the crowd.