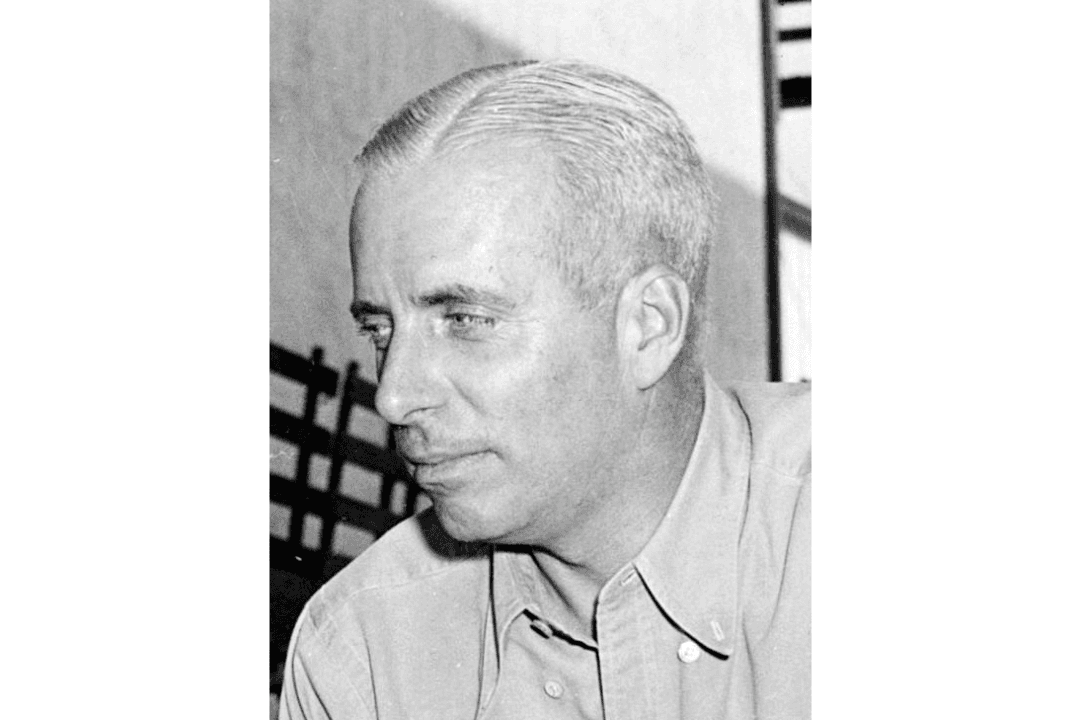

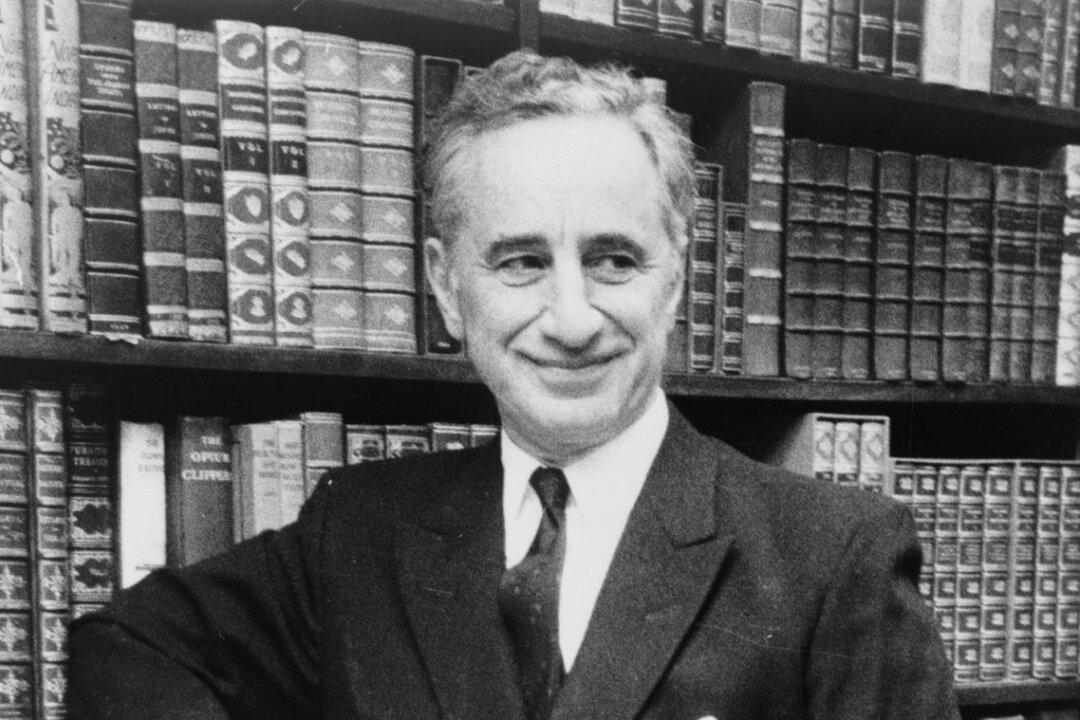

Critic James Agee called him “the most gifted American working in film.” A 1940s Vogue article claimed that his name was more familiar to moviegoers than Lubitsch or Hitchcock. Yet today, everyone knows Hitchcock but far fewer remember the man who, in only four years, wrote and directed seven of Hollywood’s most sparkling and original comedies: Preston Sturges. His genius lit up Hollywood like a shooting star in the night sky and burned out almost as quickly.

He was born Edmund Preston Biden in 1898, becoming Sturges after his stepfather, a Chicago stockbroker, adopted him. His mother, Mary, took little Preston with her to Europe where she knew many artists and celebrities, or dropped him off at a series of fancy boarding schools—an upbringing that, along with his 1930 marriage to General Foods heiress Eleanor Hutton, familiarized him with the millionaires, foreigners, and eccentrics who would later populate his films. (Eleanor grew up in her family’s 126-room Palm Beach mansion, Mar-a-Lago, which would eventually be purchased by Donald Trump.)