Albert Einstein famously said: “There are only two ways to live your life. One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle.”

‘Ordinary Angels’: How America Can Beat Health Care Problems

A hugely heartwarming (and nail-biting!) tale of the good citizens of America banding together to overcome one little girl’s medical challenges.

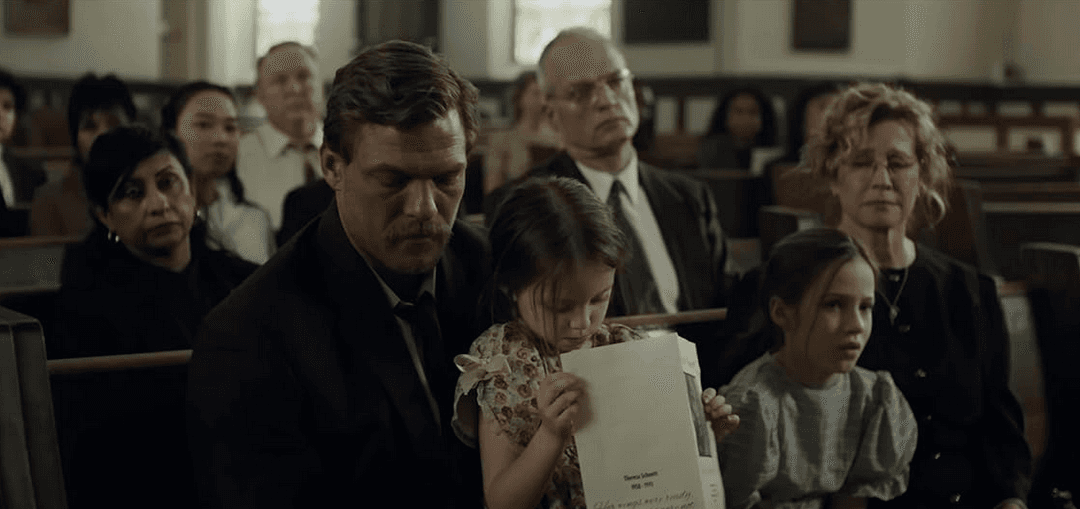

Ed (Alan Ritchson) and daughter Michelle (Emily Mitchell) in "Ordinary Angels." Allen FraserLionsgate

Mark Jackson is the senior film critic for The Epoch Times and a Rotten Tomatoes-approved critic. Mark earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy from Williams College, followed by classical theater conservatory training, and has 20 years' experience as a New York professional actor. He narrated The Epoch Times audiobook "How the Specter of Communism Is Ruling Our World," available on iTunes, Audible, and YouTube. Mark is featured in the book "How to Be a Film Critic in Five Easy Lessons" by Christopher K. Brooks. In addition to films, he enjoys Harley-Davidsons, rock-climbing, qigong, martial arts, and human rights activism.

Author’s Selected Articles