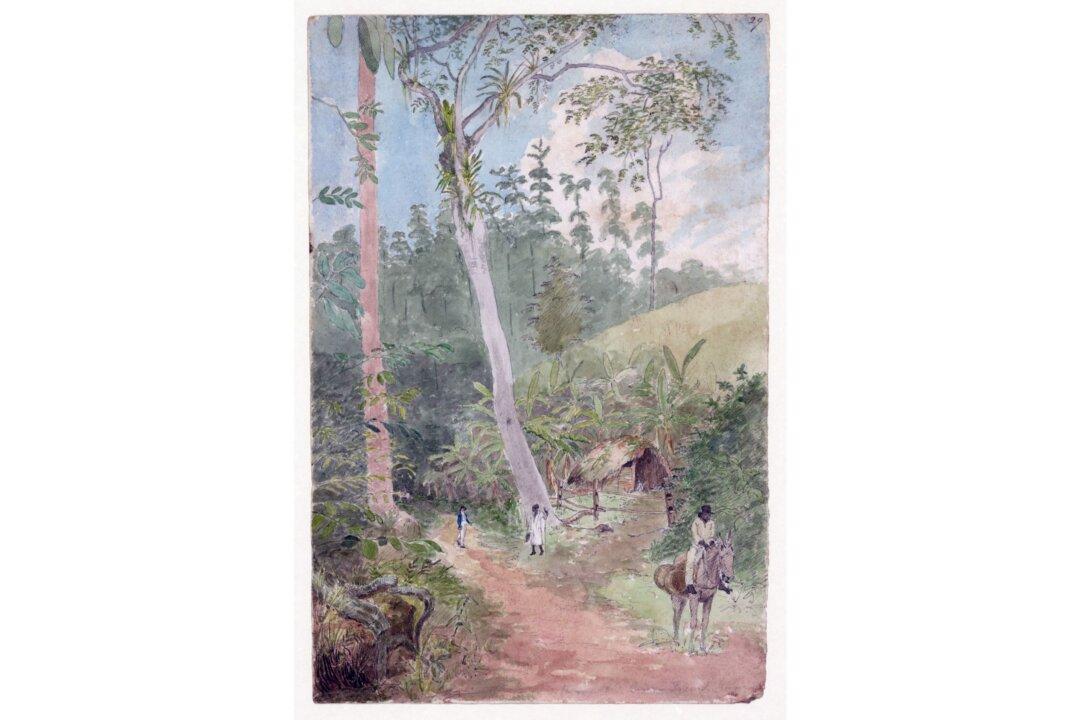

In 1590, less than 100 years after Columbus first reached the shores of San Salvador Island, José de Acosta wrote “Natural and Moral History of the Indies,” an enjoyable and informative book. In it, he considered the fascinating geography, minerals, plants, animals, and peoples of the Americas. The book demonstrates how an education in Western classics nourishes the mind, prepares it for clear-sighted observation, and even allows it to rethink classical authors’ judgments. Acosta came to appreciate the good nature, qualities, and the superiorities of New Spain and its people, despite being a clergyman of the Spanish empire who was educated to revere Old World authorities.

A photograph of Watling's Blue Hole on San Salvador Island, the island that Christopher Columbus landed on in 1492. Tillman/CC BY-SA 2.0