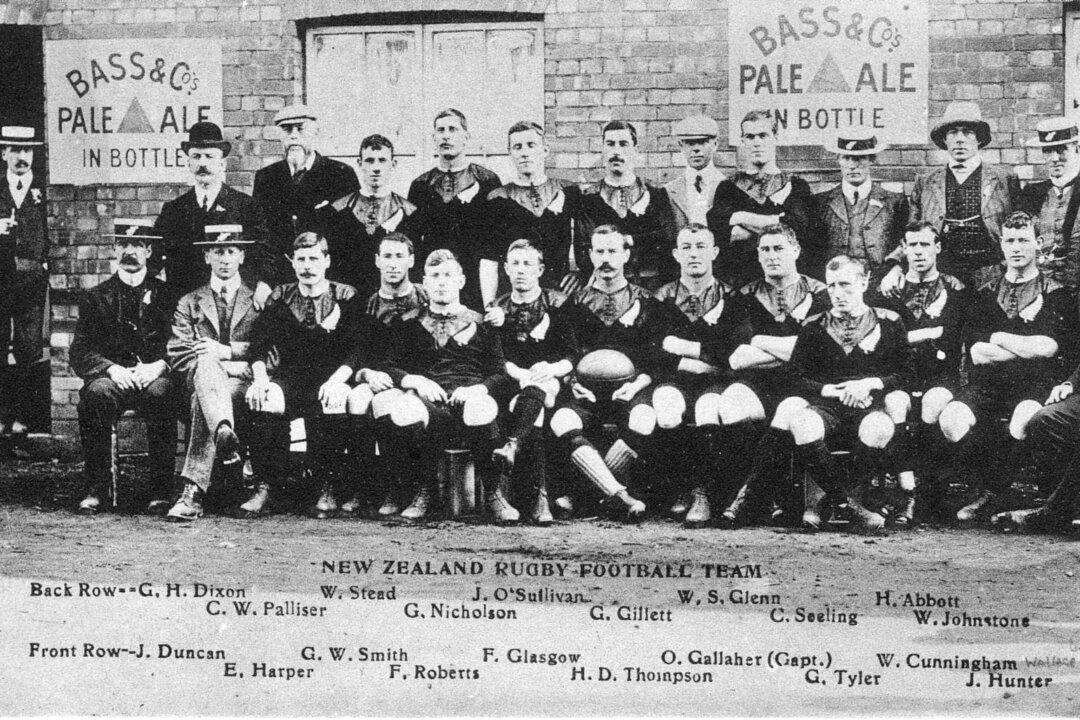

By population, New Zealand is one of the world’s smaller nations, and it has one of the smallest economies among developed nations. In the modern era, when success in sports, like most other things, is usually dictated by population and wealth, New Zealand would seem to have little chance of excelling on the world stage in any popular sport. Yet its national rugby team is not only the world’s most successful, but the most successful national team in any sport. New Zealand rugby’s open secret offers insight not only to other nations but also to communities, institutions, and even families.

Mailboxes along a rural road in Lake Hawea, New Zealand, speak to the small nation's tight-knit communities and shared rugby-focused values. Podzemnik/CC BY-SA 4.0