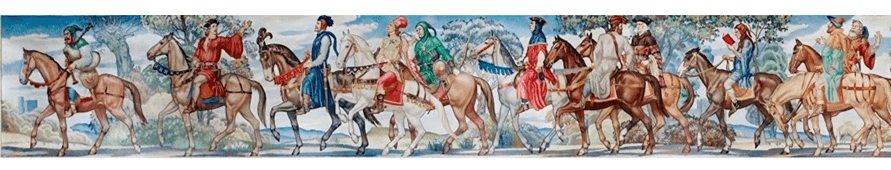

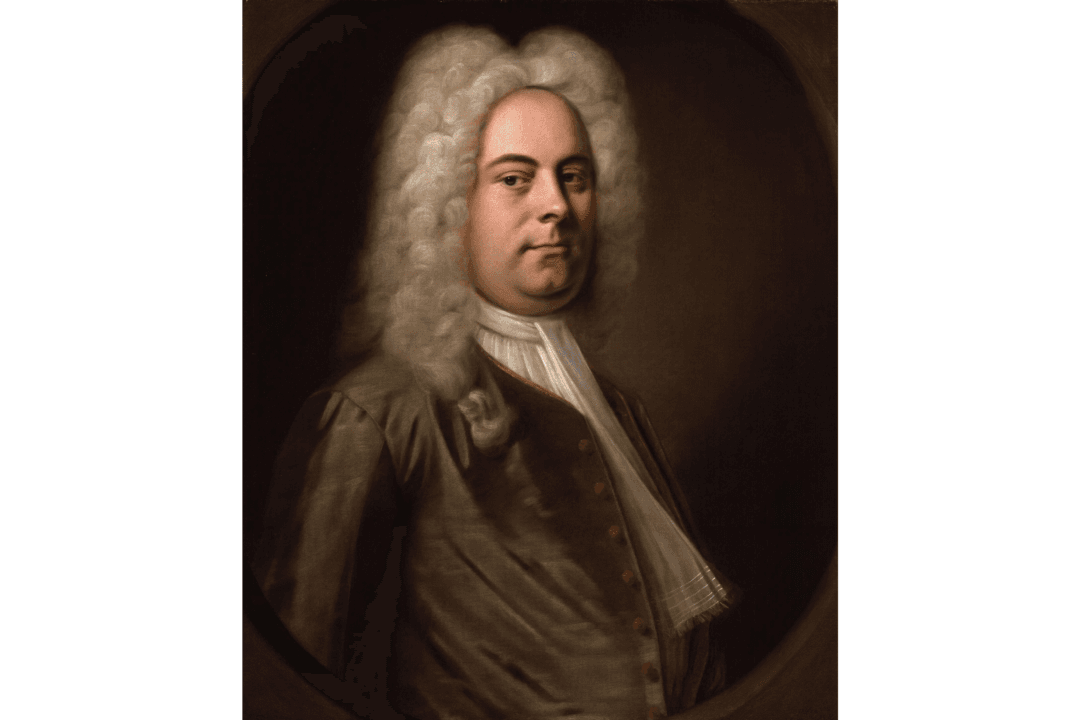

The Miller’s tale is probably the most entertaining story in the “Canterbury Tales,” a collection of 24 tales featuring 29 characters from all walks of life who are on a pilgrimage to Canterbury, England. As part of a storytelling contest, the pilgrims tell each other stories, and this framework allows Geoffrey Chaucer, the preeminent writer of the Middle Ages, to portray the various social classes and views of his time.

Each tale is a play on a specific literary genre and social class, and the Miller’s tale is no exception. Here, Robin, the Miller, tells a humorous story in the form of a French fabliau, a short, coarse, and comic tale, popular in the 12th and 13th centuries. The tale verges on a parody with its bawdy humor, popular among the lower classes in medieval England.