According to the ancients, our actions have consequences. The whole of the world expresses itself by way of cause and effect. Sometimes, however, actions that we think are good, or at least harmless, turn out to be neither. This brings up a difficult question for us: Is it better to do as little as possible to avoid doing wrong, or should we stand firm and act according to our convictions despite their consequences as long as we consider these convictions good?

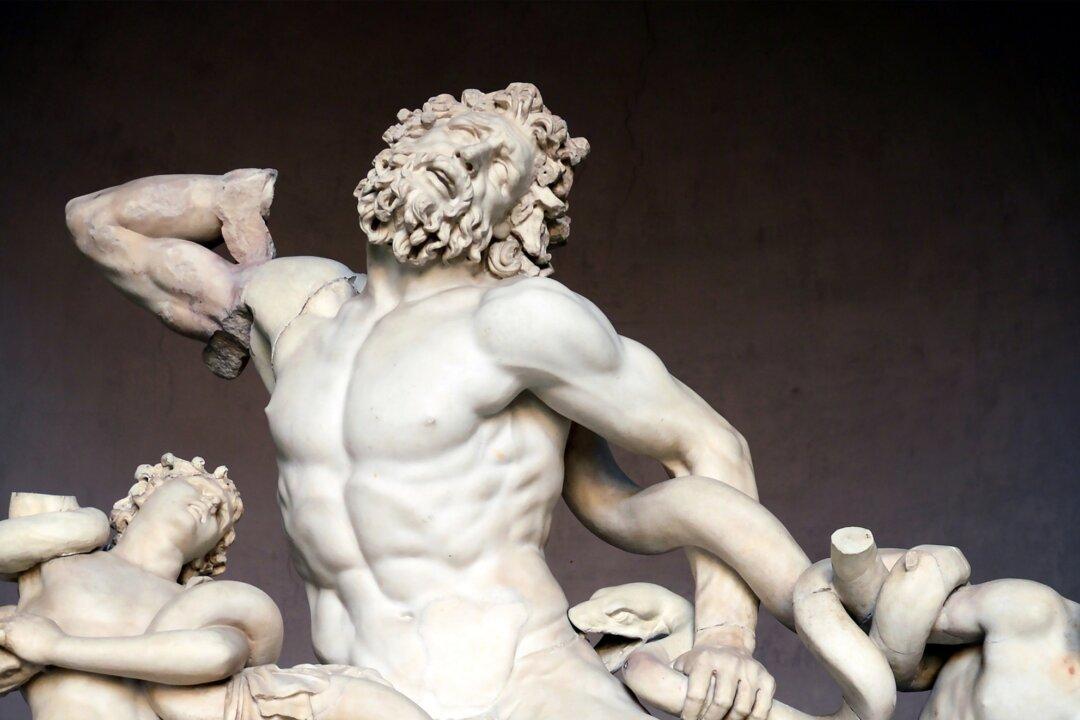

Laocoön (pronounced lay-oh-co-won) had a similar question to answer. There are two versions of his story. The first story goes as follows: Laocoön, a Trojan priest, attempts to warn the Trojans not to accept the Trojan Horse from the Greeks.