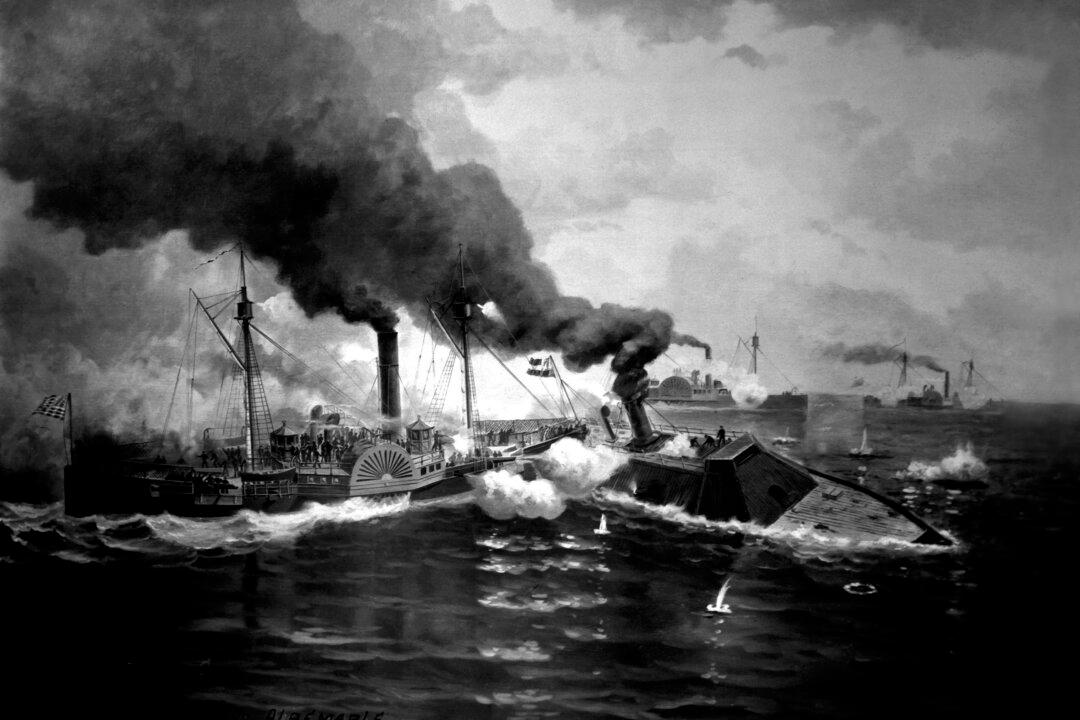

In October 1864, Union officer Lt. William Cushing became an instant hero for his leadership and daring that resulted in the destruction of CSS Albemarle, a ship which, at the time, seemed unsinkable.

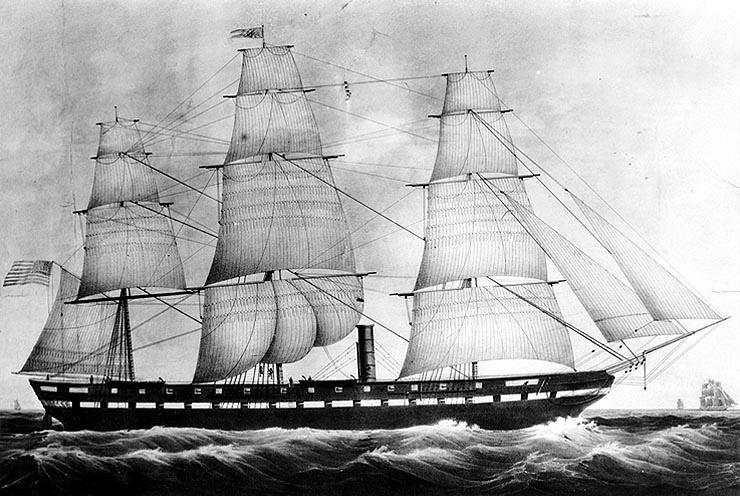

Back in early 1862, Union Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside had conquered the North Carolina Sounds. This action stunned the Confederacy. The capture of North Carolina’s Great Inland Sea took away a vast agricultural region and threatened or disrupted vital transportation links between Richmond, Virginia, and the Deep South.