The battle that changed naval warfare forevermore, the Battle of Hampton Roads, is one of history’s 10 greatest ship-to-ship engagements. No longer would wooden warships rule the waves. Armored, turreted ships with heavy rifled guns would dominate the seas for the next 75 years. Despite all the battle’s acclaim, the names of the ships and of the engagement itself are numerous and various.

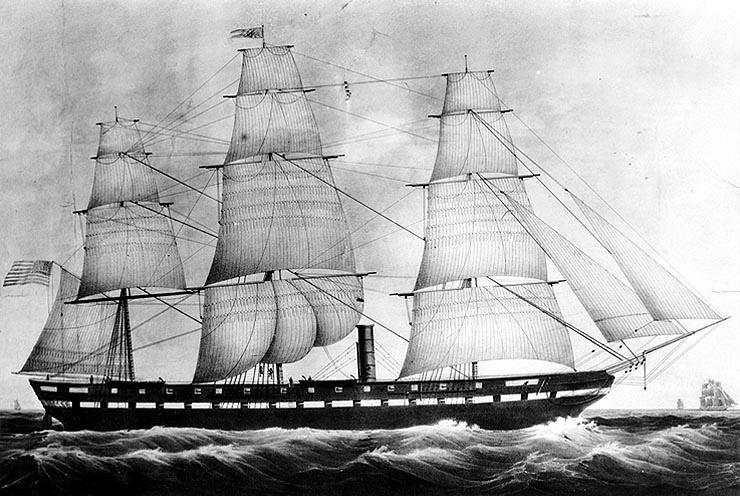

The March 8–9, 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads, similar to many other Civil War battles, has many titles. Nevertheless, no matter what you might call it, the battle is always recognized as a change agent. Often it is called “Clash of Iron,” “Monitor vs. Merrimac,” or “Battle of the Ironclads.” This naval engagement was really two distinct battles: the sinking of the wooden warships USS Cumberland and USS Congress by CSS Virginia on March 8, and the March 9 fight between the Monitor and the Virginia. Since it was fought in the harbor of Hampton Roads, Virginia, over two days and changed naval warfare forever, the battle’s name should be the Battle of Hampton Roads.