Something must have been very special about Southampton County, Virginia, as during the first quarter of the 19th century, four men of African descent, born just a few years and a few miles apart, took different paths to find freedom from the oppressive conditions of slavery. Nat Turner, Anthony Gardiner, Dred Scott, and John “Fed” Brown challenged existing norms and, in doing so, stirred the nation’s slavery debate on the way to its abolition.

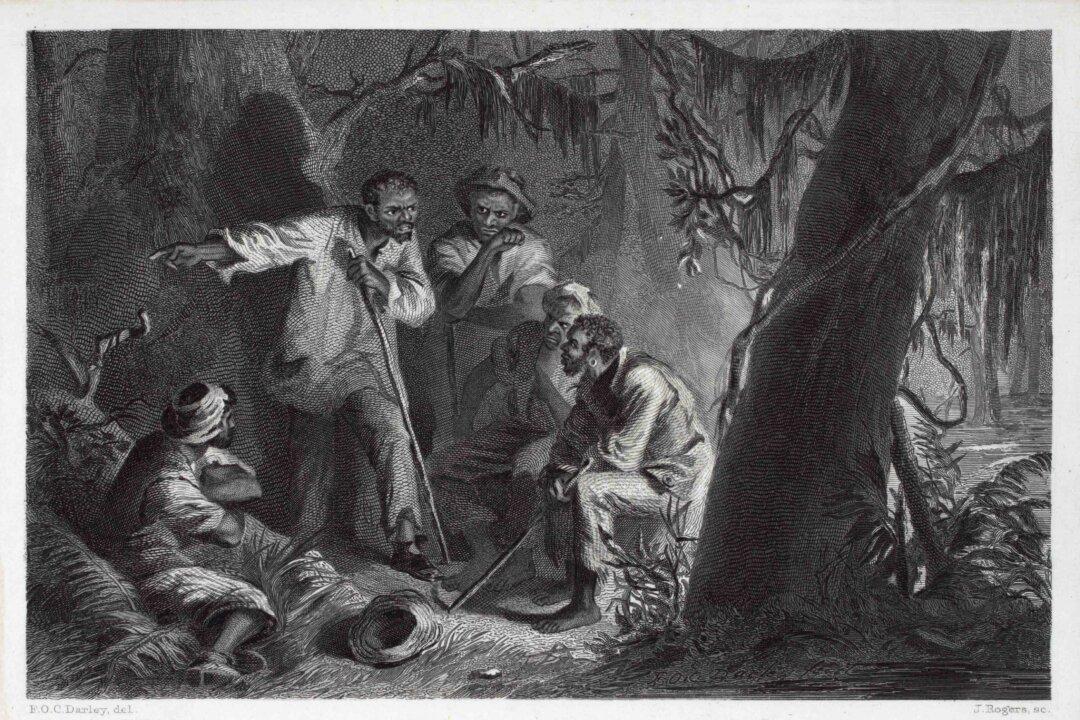

Southampton County was established in 1749. An agrarian community, its primary rivers, the Blackwater and Nottaway, flow into Albemarle Sound, not Chesapeake Bay. This circumstance limited commerce. Consequently, Southampton had few towns, just a couple of major plantations, and, mostly, small farms. The 1830 census showed the main county products were cotton, corn, brandy, and chattel people. The rapid rise of cotton cultivation in the Deep South prompted the growth of the interstate slave trade, making bondsmen Virginia’s largest export during the five decades prior to the Civil War. The census also details that there were 7,756 enslaved people of African descent in the county along with 1,745 free blacks and members of the Nottoway Tribe. The minority white population, 6,573, feared the consequences of a slave revolt.