There comes a moment in life in which we are made to reflect on who we are and who we wish to be. We stop casting blame for our circumstances and put effort into becoming the best version of ourselves. We may spend weeks, months, or even years cultivating ourselves into the heroes of our own stories.

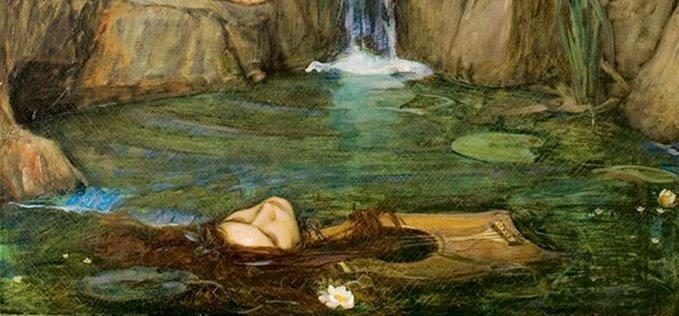

But, there’s also that moment in life in which we are seduced by our own complacency; we become lax in our efforts and fall victim to temptations for which we will later suffer.