Charles Dickens created many memorable stories. The one he loved best was also the one he spoke of from the perspective of a father: “It will be easily believed that I am a fond parent to every child of my fancy, and that no one can ever love that family as dearly as I love them. But, like many fond parents, I have in my heart of hearts a favourite child. And his name is DAVID COPPERFIELD.”

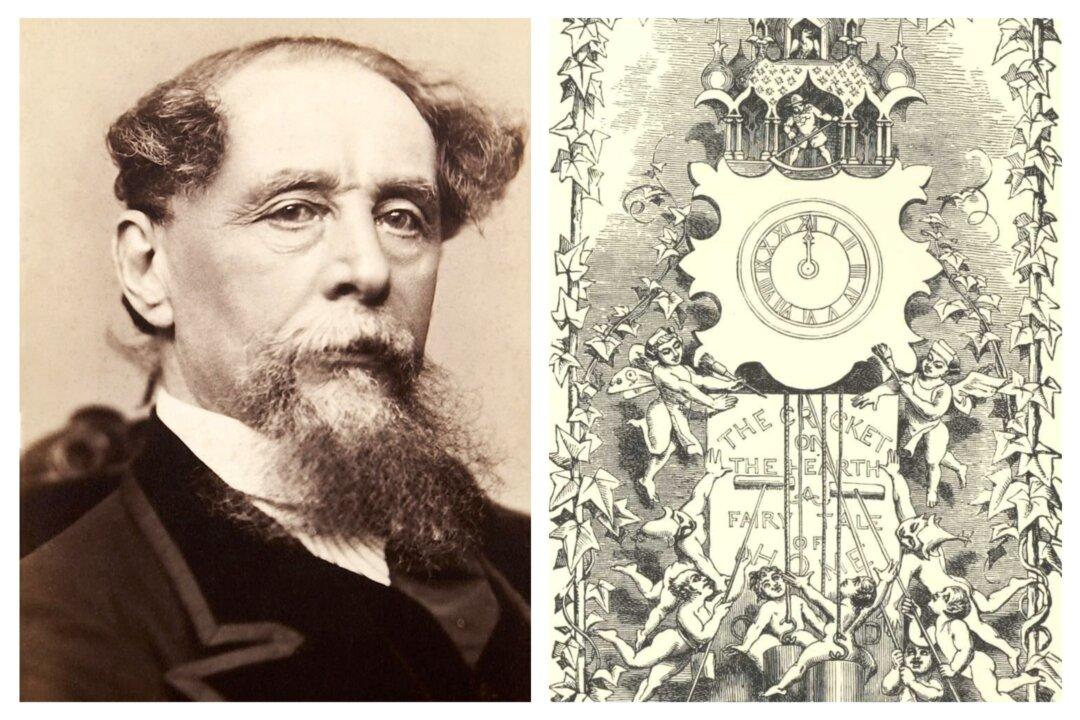

Dickens’s Favorite Work

Long acknowledged by the public and critics as one of his greatest works, “David Copperfield” inspires reflection on the meaning of fatherhood and its relationship to memory and writing.The novel chronicles the search for an absent father, as can be seen at the beginning in which the narrator of the tale, David, visits his father’s gravestone and reflects on how his father died before he was born. Just a paragraph long, these reflections are nevertheless incredibly poignant: “My father’s eyes had closed upon the light of this world six months, when mine opened on it” and his early memories of “indefinable compassion” for his father’s white tombstone.