My memories of Leonard Bernstein had mostly to do with a disparaging description by author Tom Wolfe in his scathing social commentary “Radical Chic.” After watching “Maestro,” about the life and times of the famous conductor and composer, and directed by Bradley Cooper, I suspect there’s quite a bit of truth to Wolfe’s description of Bernstein as an insufferable windbag. Except for two brief scenes, the movie bored me senseless.

Bradley Cooper Swings for the Oscar Fences in ‘Maestro’

Bradley Cooper gives a virtuoso performance in this biopic of virtuoso conductor Leonard Bernstein. Unfortunately, he focuses on sex instead of substance.

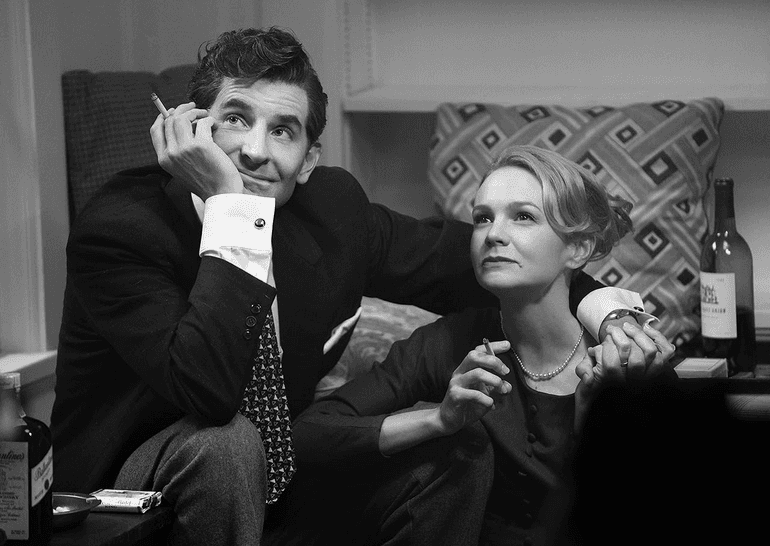

Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper) and Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan), in "Maestro." Amblin Entertainment/Netflix