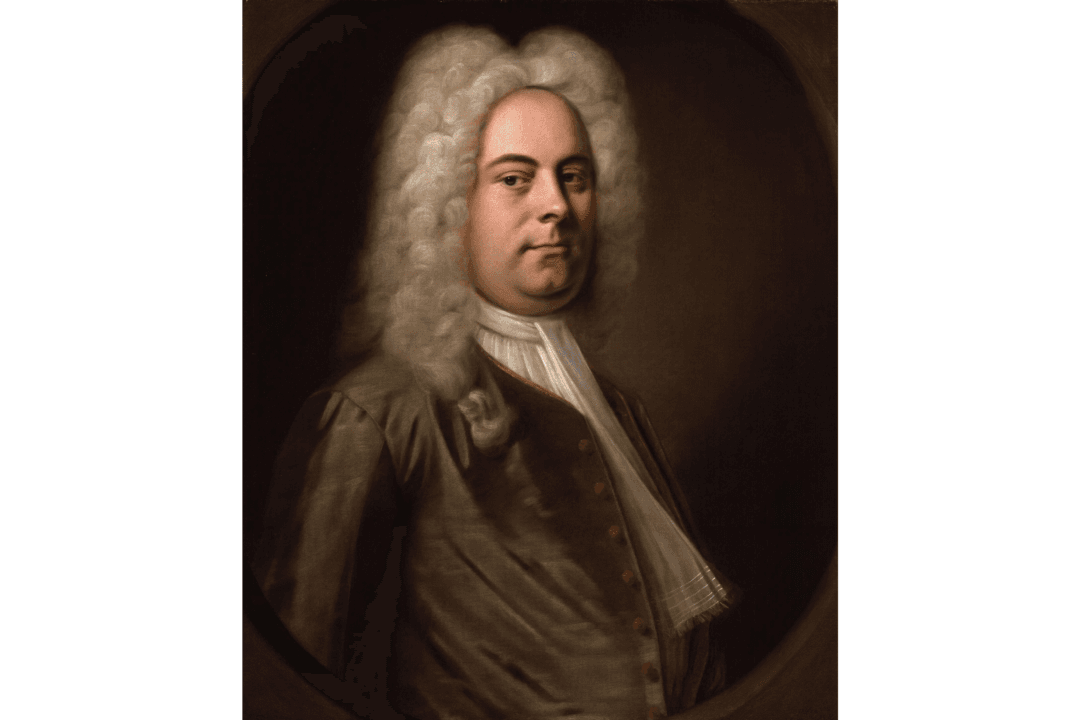

Beethoven, Handel, Mozart: These three musicians changed classical music forever. But there is another, lesser-known musician, who played a crucial part in Western classical music: Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764). A talented musician, groundbreaking theorist, and prolific Baroque composer, Rameau revolutionized French opera and all operatic music from then on.

Very little is known about Rameau’s early life. According to records, Jean-Philippe Rameau was born in Dijon, France. His father, a church organist, was said to have taught Rameau how to play the harpsichord before he could even read or write. Music seemed to be in his bones; the young Rameau attended Jesuit college, but often disrupted classes with abrupt bouts of singing.