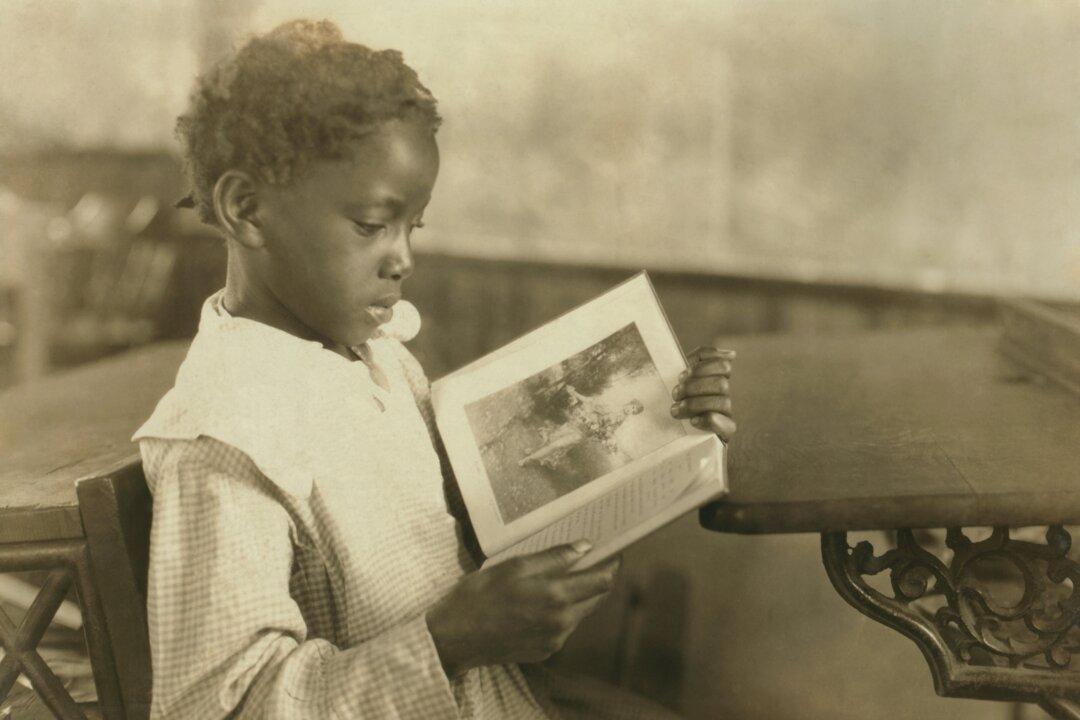

Jordan wasn’t high on my travel wish list before I read “Leap of Faith: Memoirs of an Unexpected Life” by then-Queen Noor. The book brought to life the city of Amman, the agricultural countryside, and the groups of women artisans the queen had helped organize into workshops so they could become independent. When I finished reading, I moved Jordan to the top of my list, and then finally I actually went.

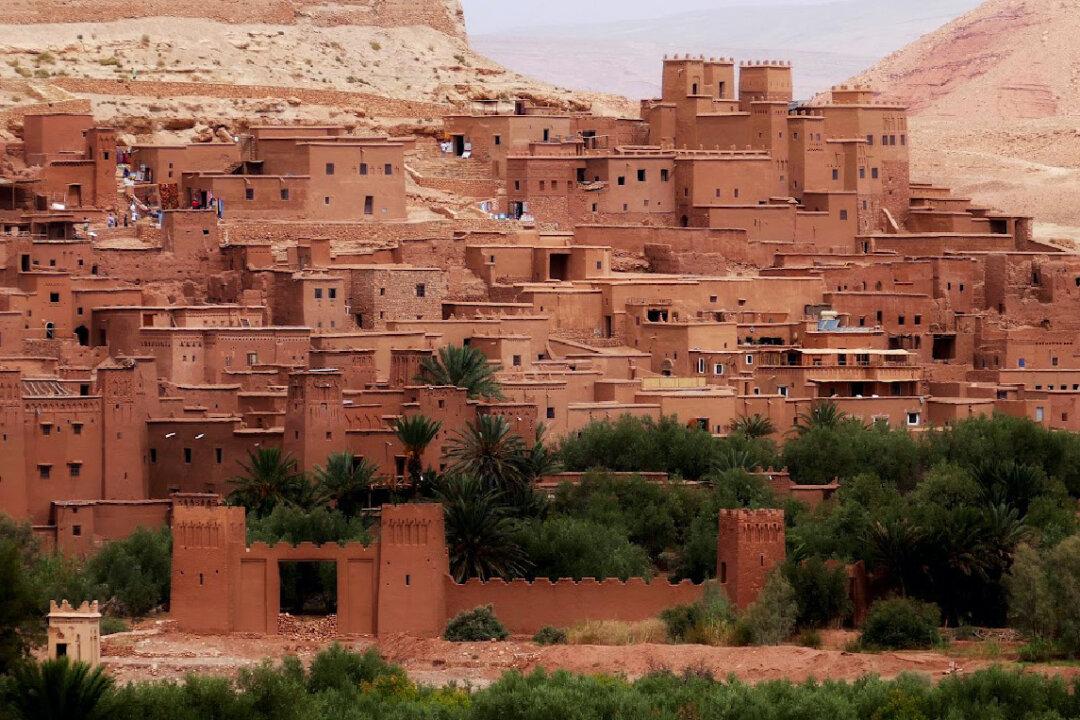

What I remembered most about the book was the description of the pink landscape of Petra, a once-thriving metropolis that was largely abandoned by the eighth century A.D. and is now an archaeological treasure. So when my husband and I arrived in the country, that’s where we went first. The adventure involved a four-hour coach trip from Amman on the Desert Highway to Wadi Musa, where we spent the night. The next morning, it was just a short walk to Petra’s entrance, and from then on, we experienced the very magic the queen had conjured up in her book.

To get to the actual city requires an easy mile-long walk through the Siq, which looks like a slot canyon but is actually a geological fault that branches off of the Bab as-Siq (Gateway to the Siq) valley. The walls here range from 299 to 597 feet tall, and the pathway is only 10 feet across. Some cobblestones laid by the Romans during the occupation that began in the year 106 are still intact, as are the ceramic pipes they put into place for the efficient use of water.