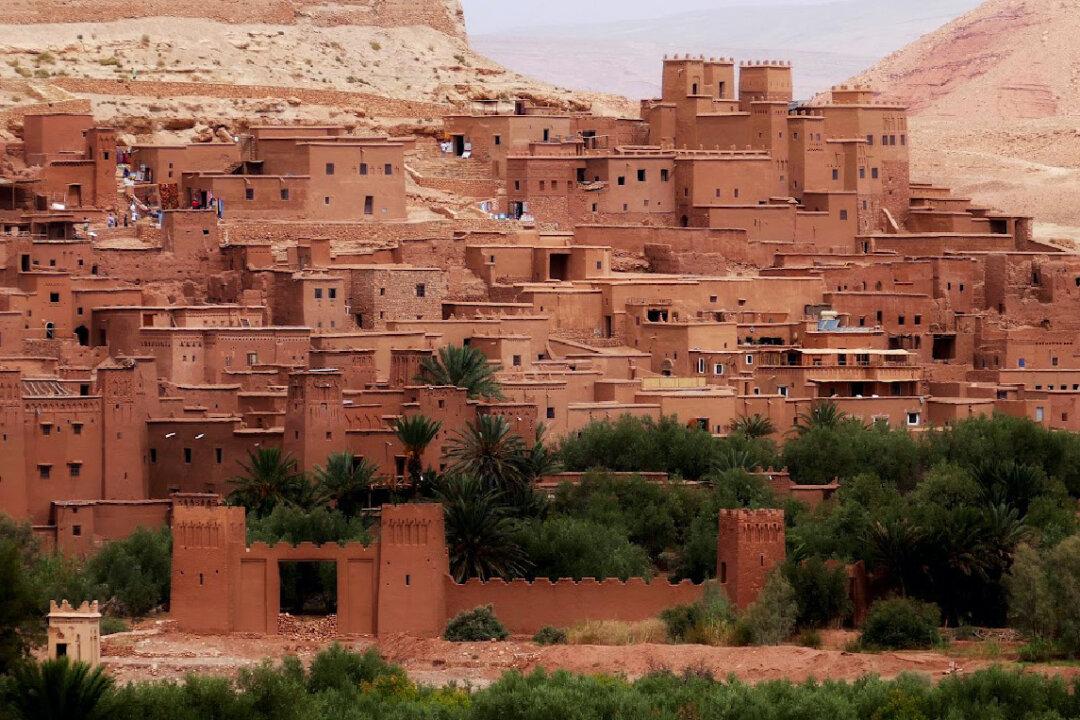

A city in the east-central part of Indiana might not be the first place you'd think to look for Black history. “What about Atlanta? Or Little Rock? Or Selma?” you might ask. But take a moment to look at a map of the state, and it’s easy to see why this place is as important to African American history as all of those others.

The Ohio River creates the ruffly southern border that separates Indiana from Kentucky, and freedom-seeking slaves had to cross it in order to get to Michigan and Canada, where they could find work and be safe. Often they did this when the water was frozen in the winter to avoid drowning. Once they had arrived at such cities as Madison and Jeffersonville, the trip north took them straight through Richmond.