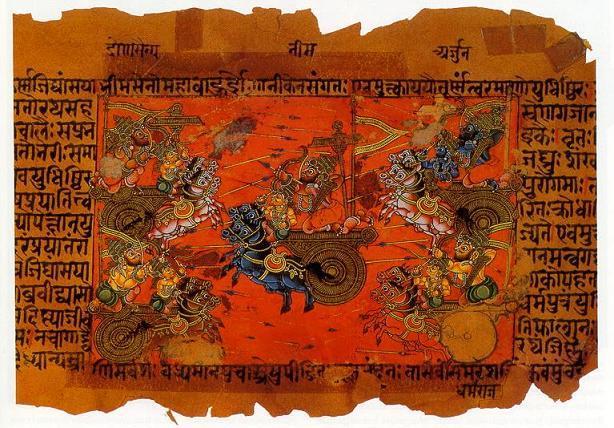

The Bhagavad Gita (or Gita) contains much profound wisdom. However, the key event leading to the victory of Arjuna over Duryodhana in the Gita occurs in a prequel incident outlined in the Indian epic the Mahabharata. This incident is fascinating because it is so pregnant with multiple meanings that resonate with us today. In describing this, one has to strip away much of the complexity and detail that the Indian epic delights in, but the central issues are clear.

Relationships between Duryodhana and his family, the Kauravas, and Arjuna and his family, the Pandavas, have reached a critically low point. At stake is who rules the kingdom. Duryodhana (whose name in Sanskrit means “extremely hard”) is advised to consult and seek help from Krishna, the living god and embodiment of Vishnu (for some Indians, the supreme deity). Arjuna (which means “white or clear”) has the same idea. There is the suggestion that whoever gets to Krishna’s house first receives a special gift.