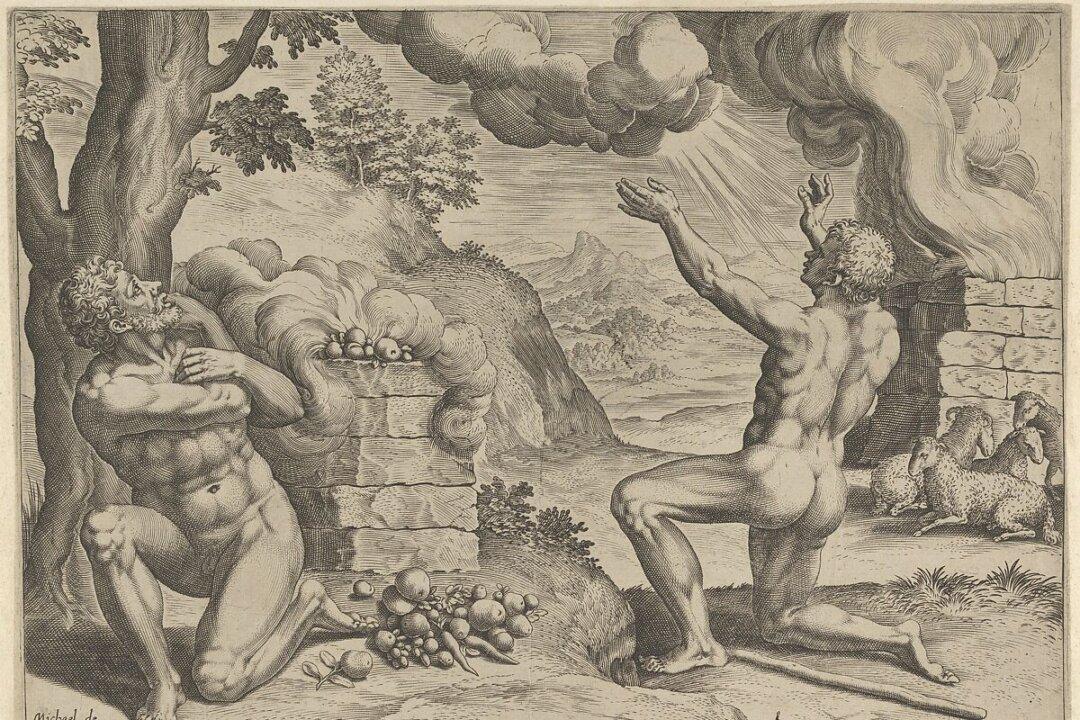

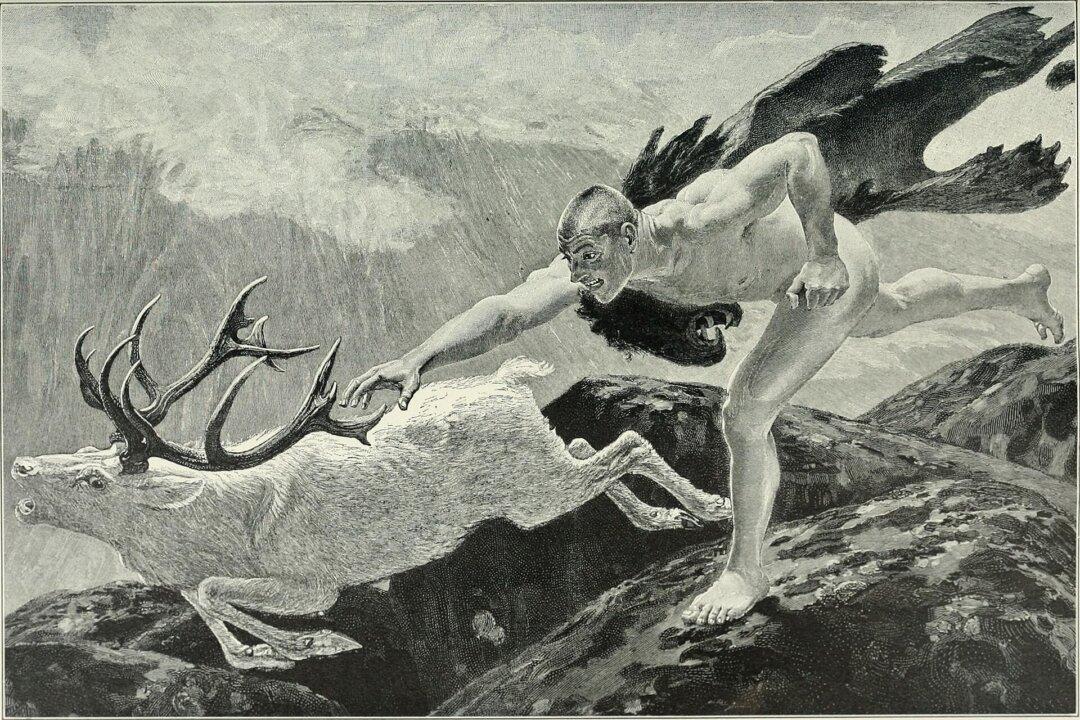

From the beginning of human history, we’ve been captivated by the phenomenon of twins. Consider four classic examples: Castor and Pollux (the Gemini twins from Greek mythology), Romulus and Remus (Romulus being the legendary founder of Rome), Jacob and Esau (Jacob, who became Israel and wrestled with God), and Cain and Abel (the sons of Adam and Eve). While Cain and Abel aren’t explicitly denoted as twins, tradition suggests they were, and their dynamic, intertwined relationship strongly implies twinship. Why this ancient fascination?

Double the Curiosity

One reason lies in the perceived duality of human nature. Shakespeare, exploring twinship in several plays, captured this duality in “Hamlet”:“What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty! In form and moving, how express and admirable! In action, how like an angel, in apprehension, how like a god! The beauty of the world, the paragon of animals—and yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? Man delights not me.”