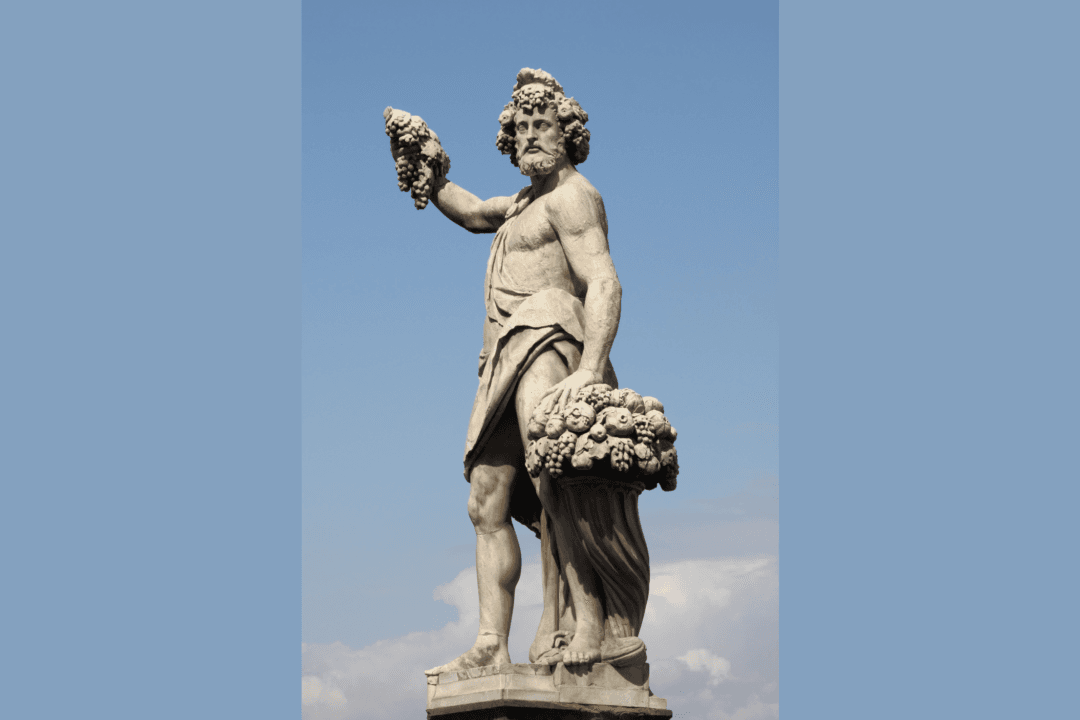

In the 20th and 21st centuries, Western culture has displayed an abundance of Dionysian behavior. One aspect of the cult of the Ancient Greek god Dionysus is wine drinking and ecstasy, especially through sexual orgies. In myths, Dionysus traveled the world, often accompanied by his wild retinue of satyrs and maenads, who surrendered themselves to divine madness. If this sounds like a rock and roll tour that the young (and the not-so-young) crave, adore and worship, it’s because it is just like that.

Apollo Versus Dionysius

In the 19th century, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche posited the opposition between the gods Dionysus and Apollo in a number of his works, beginning with “The Birth of Tragedy.” That opposition was potentially responsible for much evil in the succeeding century. Leaving aside the question of how much Hitler and his henchmen were influenced by, or misappropriated and misinterpreted Nietzschean teachings, the fact remains that the dichotomy that Nietzsche outlined between Apollo—the god of order, rationality, harmony, reason, clarity, individuality and all that gives life meaning through structured beauty—and Dionysus, who represents chaos, passion, emotion, irrationality, and collective unity, is true.Coming at the end of the 19th century, Nietzsche noticed a historical phenomenon: The 18th century, with the beginnings of the Age of Enlightenment and reason, was in one sense Apollonian. It seems that even rationality, order, and structure became tired and spiritless and that something needed to happen to refresh life. This something was represented by the chaos of the god Dionysius. As if in reaction to the Age of Enlightenment, the Romantic movement began (in earnest in England in 1798 with the publication of William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge’s “Lyrical Ballads”) and swept away the god of reason with a god of feeling and irrationality.