Modern American society still talks about and references the American Revolution all the time. Its battlefields are well preserved and marked, its literature is still invoked in modern political campaigns and speeches, its symbols and quotes and prominent figures are everywhere in stone and bronze and steel and ink—at least for now. Perhaps the individual motivations for participation in violent struggle were as numerous as the individuals who participated. On a certain level, then, asking, “What were they fighting for?” is only inviting inevitable oversimplification. Even so, an attempt to spell out some of what provoked men and women to shoot at each other (or to support others in the endeavor) may serve to at least demonstrate the wide range of impulses driving the American Revolutionary War. War, like other historical phenomena, is complicated. It’s muddy.

Those Who Served

Letters were exchanged throughout the war between Massachusetts shoemaker Joseph Hodgkins, a Minuteman leader and veteran of Bunker Hill, and his wife Sarah. In April 1776, he wrote Sarah, “I am willing to serve my country in the best way and manner that I am capable of, and as our enemy are gone from us, I expect I must follow them. … I would not be understood that I should choose to march, but as I am engaged in this glorious cause, I am [willing] to go where I am called.” Hodgkins would go on to fight at the Battle of Long Island, the Battle of Harlem Heights, the Battle of White Plains, the Battle of Trenton, and the Battles of Saratoga. Hodgkins left his wife and children alone—often to Sarah’s chagrin—in order to “serve [his] country,” i.e. Massachusetts.

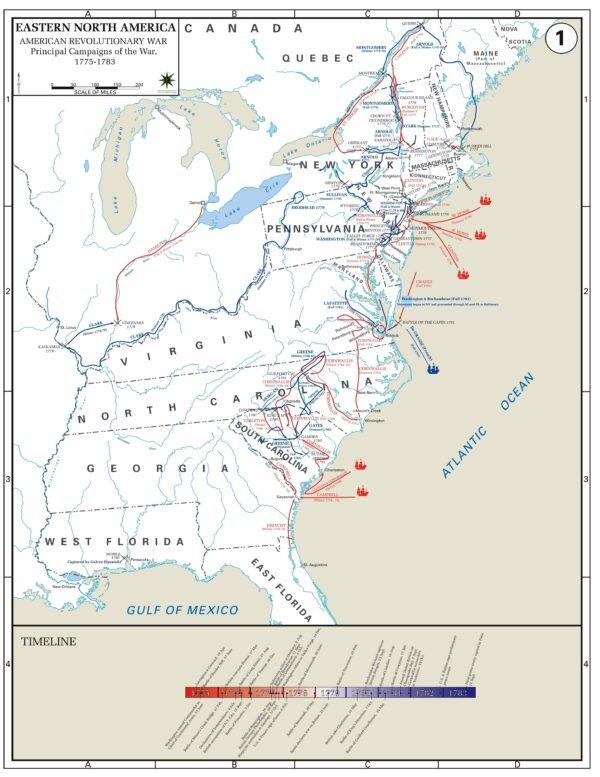

A map detailing the major campaigns of the American Revolutionary War.

Public Domain

Public Domain