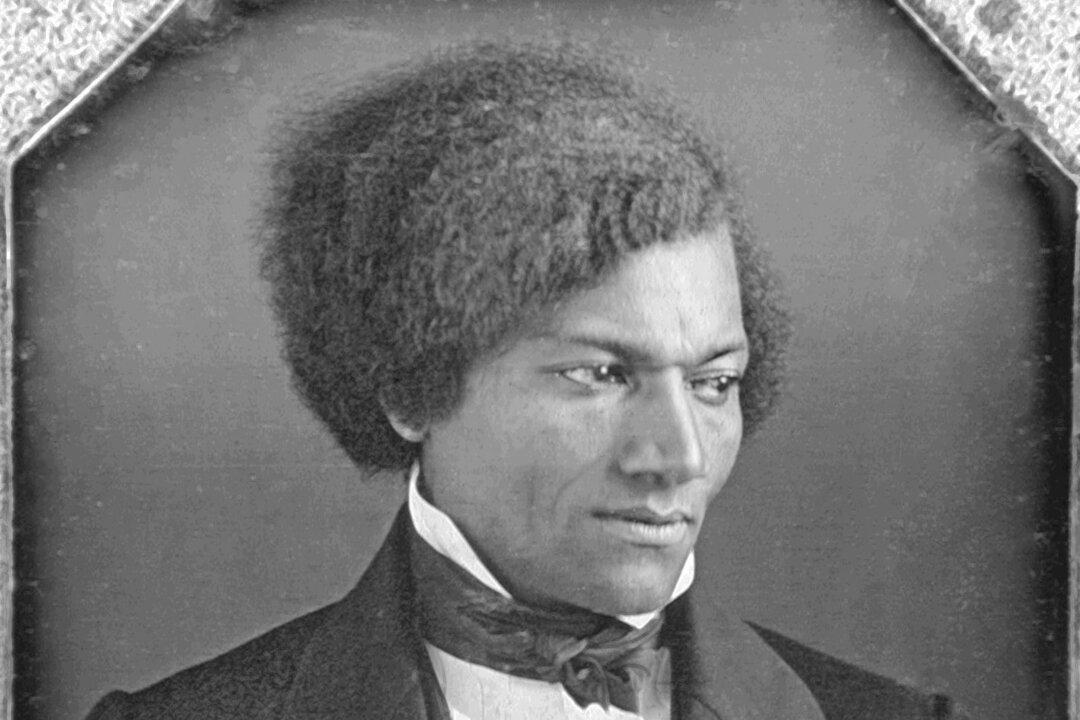

In 1838, a Maryland slave named Frederick Bailey, age 20, escaped from bondage, making use of the recently constructed Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad. By rail, Frederick effected his flight in only one day. “A new world had opened upon me,” he wrote later, recalling the moment he first stood upon free soil. “If life is more than breath, and the ‘quick round of blood,’ I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life.” Later that year, he was married to the free black woman who had helped him escape, and the couple—who had adopted the surname “Johnson”—settled in Massachusetts. Here, Frederick Johnson became a licensed preacher, and in time he and his wife adopted a new last name: Douglass.

In Massachusetts, Frederick Douglass was introduced to The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison’s weekly paper, which cultivated within him an even more abiding hatred of slavery than he’d harbored before. Douglass had learned to read as a child, thanks to his own ingenuity and some young friends. Of this childhood experience he later recounted:

“The plan which I adopted, and the one by which I was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street. As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers. With their kindly aid, obtained at different times and in different places, I finally succeeded in learning to read.”Douglass’ subscription to “The Liberator” marks a watershed in his life. The former slave later explained:

“From this time, I was brought into contact with the mind of Mr. Garrison, and his paper took a place in my heart, second only to the Bible. It detested slavery, and made no truce with traffickers in the bodies and souls of men. It preached human brotherhood; it exposed hypocrisy and wickedness in high places; it denounced oppression, and with all the solemnity of “Thus saith the Lord,” demanded the complete emancipation of my race. I loved this paper and its editor. He seemed to me, an all-sufficient match for every opponent, whether they spoke in the name of the law, or the gospel. His words were full of holy fire, and straight to the point.”