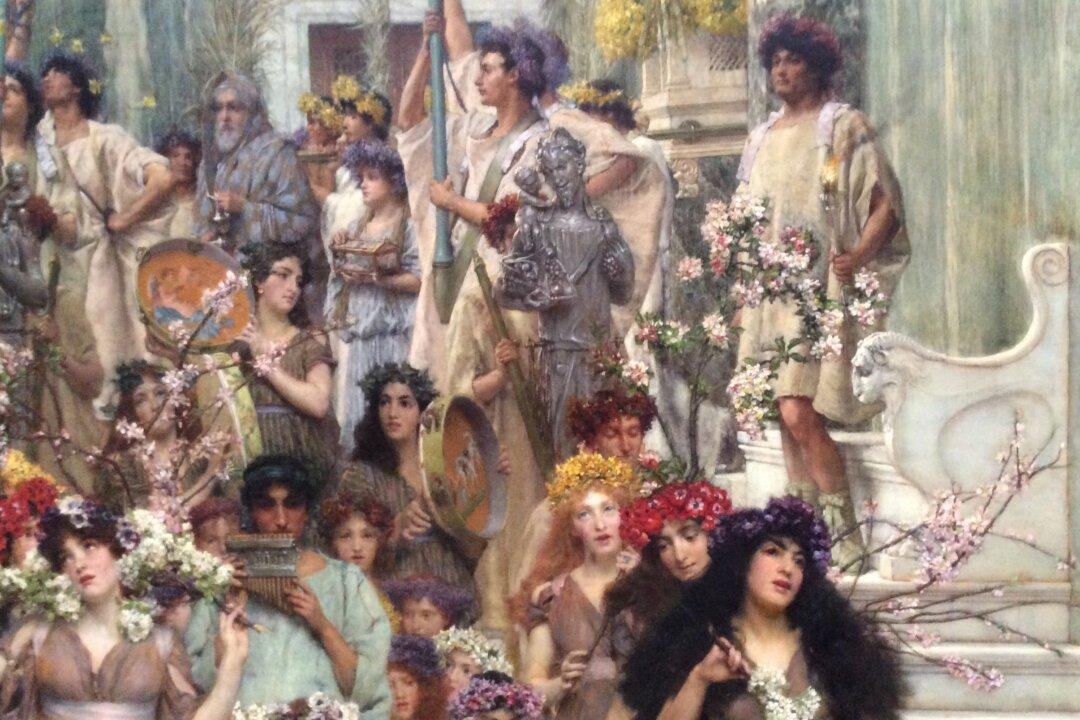

HOLLYWOOD, Calif.—It seemed entirely fitting to watch “Wendy,” the rambunctious, mythical retelling of “Peter Pan,” on the mercurial Leap Day, followed by a Q and A with its director Behn Zeitlin.

The film is set in a roadside diner, a home by the railroad tracks, where Wendy and her twin brothers are enticed to follow little Peter Pan, who is jumping from train car to train car along the tops of a massive locomotive that passes their house, shaking all of the windows and doors. The train itself seems a creature of the imagination.