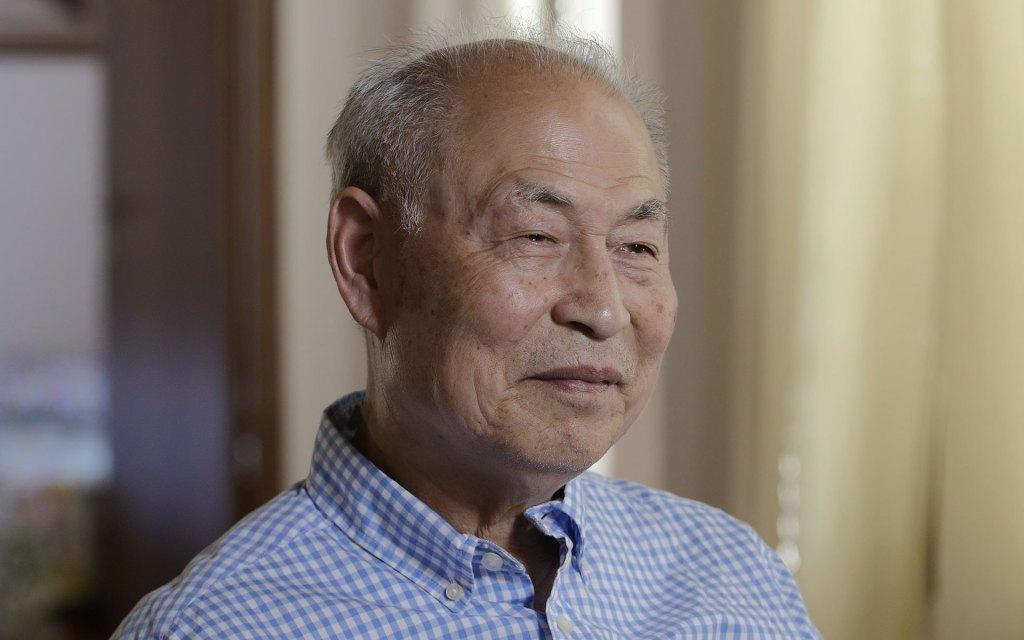

“This whole project was a blessing for me,” said Kacey Cox, the Toronto-based director and producer of “Finding Manny.” “I grew so much, personally and in my understanding of what the Jewish people experienced in the Holocaust: meeting a guy like Manny and spending time with him, learning about his personal outlook, his philosophies, and his sense of optimism.”

Exclusive: Director Kacey Cox Talks ‘Finding Manny’

Behind the Scenes With the Director of the New Holocaust Documentary 'Finding Manny'

|Updated: