We live in secular times. One of our former presidents, Calvin Coolidge, said that “the business of America is business." Certainly, making and taking money seems to be heavy on the minds of many people. Even in music, a prominent contemporary composer remarked, “I began working in a record store when I was a kid. The first thing I knew about music was that you sold it; in other words, people paid for it.”

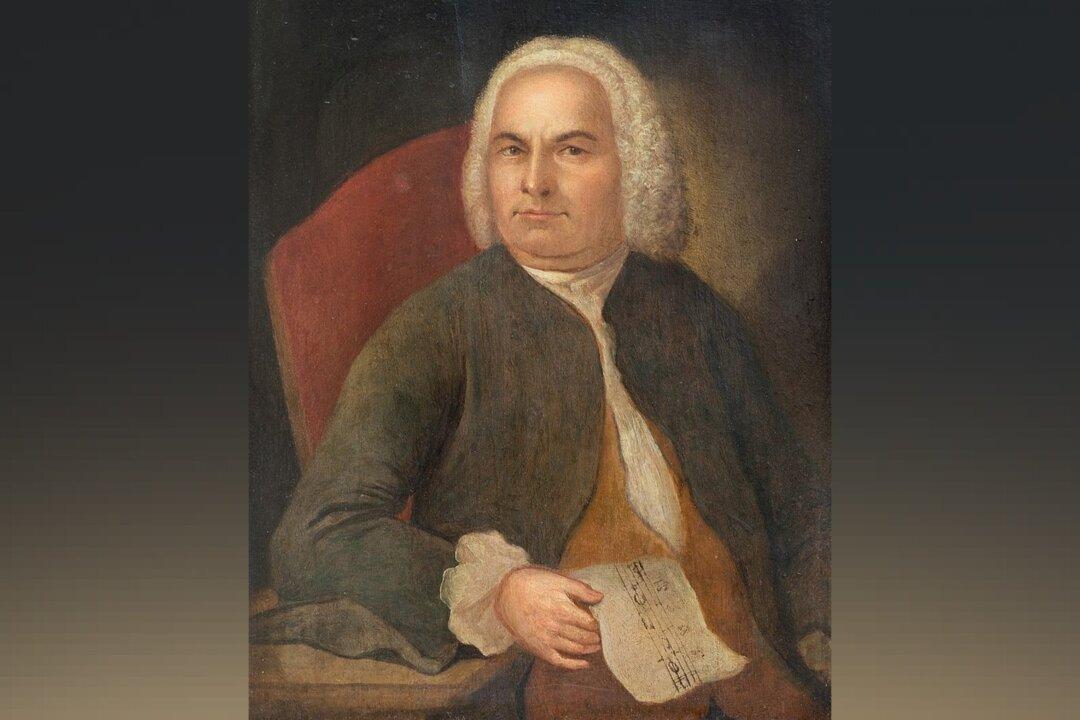

Let us compare this way of thinking with that of Johann Sebastian Bach, a citizen of another country, from another time, almost 400 years past. His works often bore the inscription “Only for the glory of God.” In the margins of books from his personal library are entries such as “Where there is devotional music, God with His grace is always present,” and “music has been mandated by God’s spirit.”