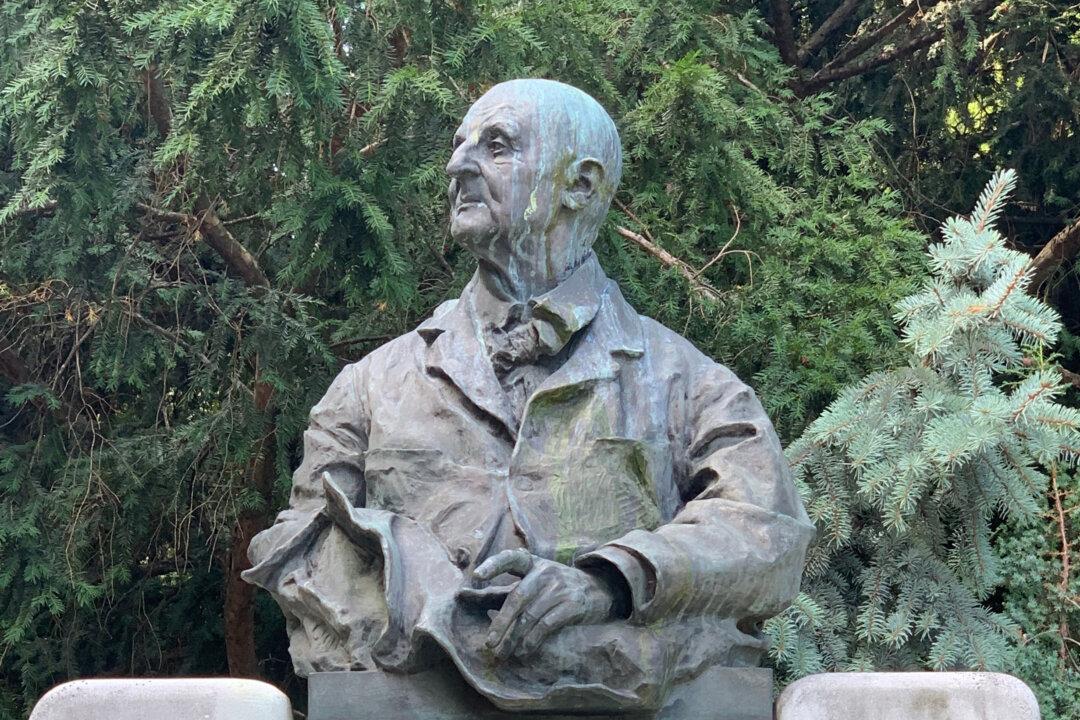

It is curious that beautiful works of art are often created by people who are not so beautiful themselves. Austrian composer Anton Bruckner’s homeliness and awkward ways seemed humorous to even his most devoted friends.

Beginnings

Until age 46, Bruckner (1824–1896) lived in the Alpine foothills of Upper Austria where the land seemed vast and the sky infinite. Bruckner was raised in the Church, in the faith of his forefathers, and theirs was a faith unshakable, unchanged from medieval times. Magnificent nature and the Church constituted the bedrock of his personality to his last breath.He knew poverty and humiliation at the age of 12 after his father’s death, as his mother was left without an income and turned to farm work to feed and shelter her family. Four years later, young Bruckner became an assistant schoolteacher in the small village of Windhaag. His duties, as well as teaching, included playing the organ at church services, ringing the church bells each morning at 4:00, and shoveling manure in the fields. His salary was so meager that he had to play the violin late into the night for parties and village celebrations. Complaints and insults were daily fare from his boorish supervisor. This cruel material life lay in great contrast to his inner spiritual life—one of wonder, beauty, and kindness.