“We don’t go to art for information. Rather it’s the experience.”—Roger Scruton, philosopher

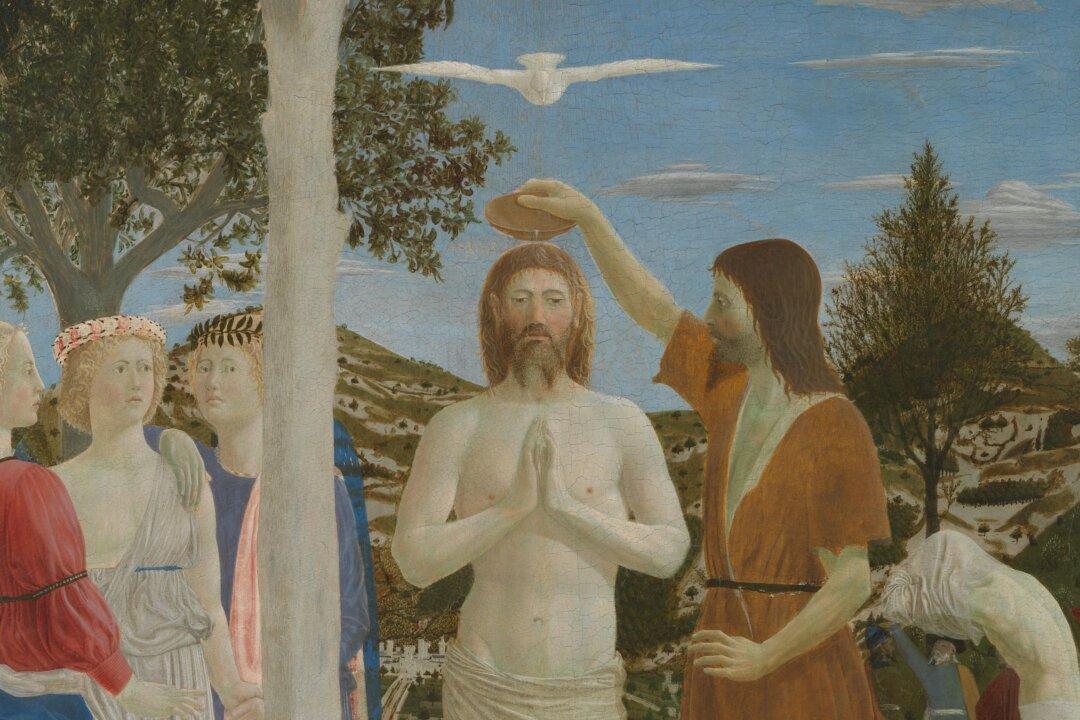

Piero della Francesca’s “The Baptism of Christ,” which hangs in the National Gallery in London’s Trafalgar Square, was rather like a personal shrine to me. I visited it frequently “for the experience.”