Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication. —Leonardo da Vinci

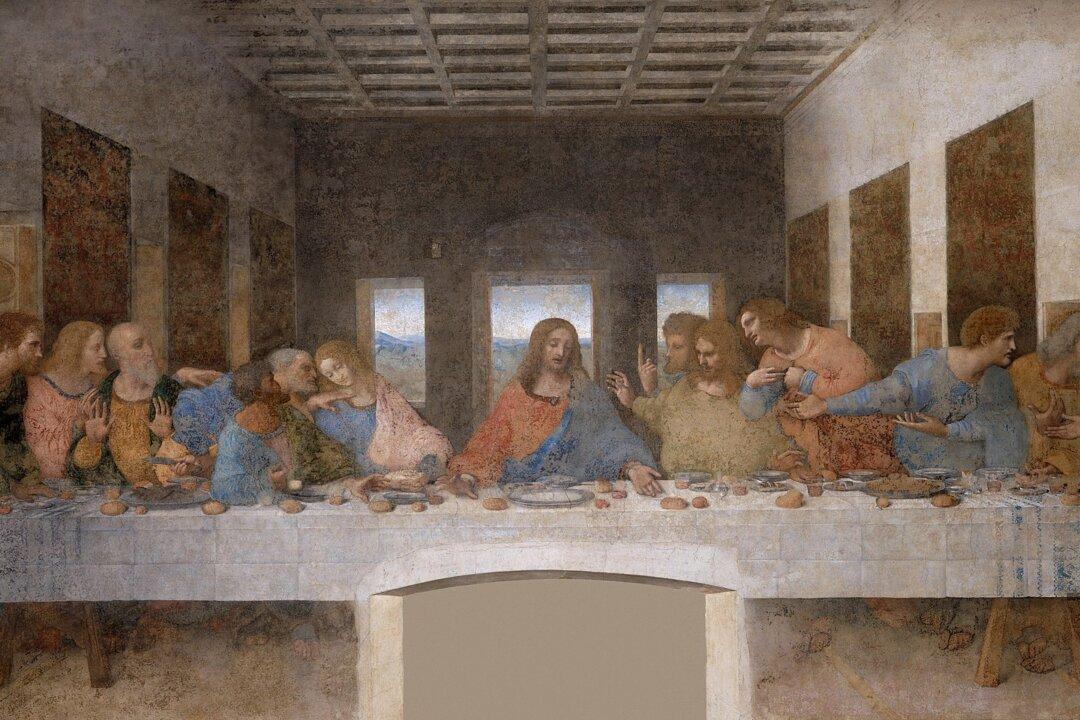

I once saw Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.” Then, it was still possible to wander into the UNESCO World Heritage site of the Church and Dominican Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy, and see the mural.What do I remember? The silence. The profound mystery. To weep at such majesty would be sentimental. As Leonardo himself said, “Tears come from the heart and not from the brain.” Leonardo painted the most dramatic moment in time, without drama. All is contained within the strictures of mathematical perspective.