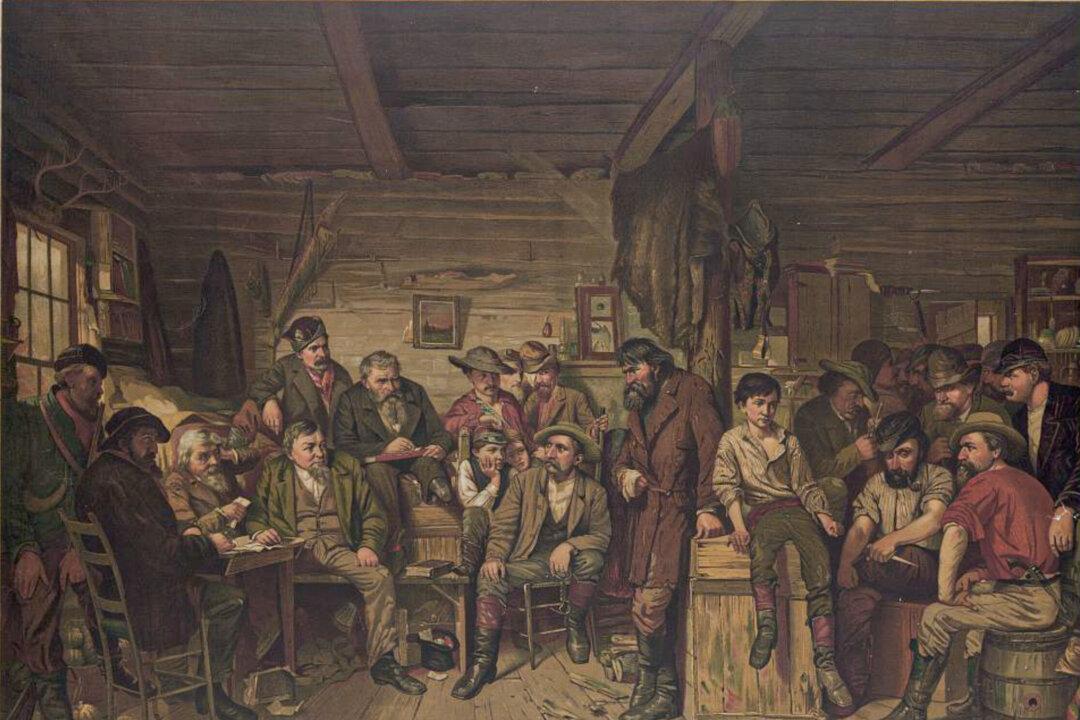

Oklahoma and Indian Territories were among the last frontiers of the wild and woolly American West. Hordes of legal fugitives and an assortment of unsavory characters flocked to the region when it was thrown open for settlement during a series of land runs. Col. D.F. MacMartin describes it best in his book “Thirty Years in Hell: Or, the Confessions of a Drug Fiend”:

“History has never recorded an opening of government land whereon there was assembled such a rash and motley colony of gamblers, cut-throats, refugees, demimondaines, bootleggers and high hat and low pressure crooks.”