Having lived through oppression herself as a child during Poland’s post-Stalinist era lends credence to one of her paintings in which she portrays the “often overlooked” suffering of the children whose parents have been persecuted by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

“Children are an easy target after they take the parents away,“ Australian artist Barbara Schafer told The Epoch Times. ”Chinese children are being bullied for their faith, many are excluded from school, punished for attending church and religious activities outside of school, forced into reciting anti-religion and pro-atheism slogans, and coerced into signing documents renouncing their faith.”

Schafer, now 68, was only 12 years old when her own father, a glassblower, died in communist-controlled Poland in 1965 after having been incarcerated in a concentration camp during World War II; he survived the camp, but not the poor health he suffered for years afterward.

“Countless Polish people died in Soviet gulags and from starvation,” Schafer said. “At the same time, double-size trains were going 24 hours a day to the Soviet Union, stealing everything from Poland they desired.”

Growing Up in Communist Poland

Born in Skawina near Krakow in 1953, just eight years after the end of World War II, Schafer said it was “another dark page in our history” and “a day the Polish people will never forget” when the allies handed over the territories of Poland and other Eastern European countries to the Soviet regime at the Yalta Conference in February 1945.“The traitors and the party members lived in extreme wealth and opulence,” she said. “As for the rest of the people, some were still happy because the war had ended, they shared their joys and drowned their sorrows in vodka.”

For the Polish people, happiness over the war’s end was overshadowed by the reality of living under their new communist government, and Schafer would grow up learning what it meant to suffer from oppression.

“Many of my family members have been persecuted by the ruthless, tyrannical communist regime,” said Schafer, who’s lived in Melbourne since 1987 after first having migrated from Poland to New Zealand 10 years prior with her husband, an aircraft engineer, when she was 24.

As a child, believing that the Polish media was working for the people, young Schafer had once written letters to the newspaper and radio expressing her concerns—and suffered the bitter consequences. “My mother was punished for it,” she said.

Freedom of information, she discovered, was nonexistent. “Every letter that we got from the West was opened and some information in it was painted over with black ink.”

Schafer recalled how, from an early age, she used to stand guard at the window while her father listened to Radio Free Europe or Voice of America, telling him who was passing by, because there was a prison sentence for it.

‘'Some people could not be trusted,” she said.

“As the communist rules were infiltrating every aspect of our society, people became more demoralized, arrogant, lazy, and self-centered. Shops were getting more and more empty. Corruption and bribes were widespread, and the ration cards for food were introduced.”

Referring to communist indoctrination in schools, Schafer, now a mother and grandmother, said that the Polish children all knew that some teachers were “lying to keep their jobs,” but in truth, they really wished to hold on to their traditions.

It was determined faith that gave the Polish people hope, she said.

“What the Soviets could not do in Poland was to destroy the faith in God that kept the Polish people going,” she said. “The government knew that destroying churches would lead to their demise. Unfortunately, they had spies among the clergy as well.”

She said many of the good clergymen were persecuted and killed for standing against communism.

By 1960, the Soviets had built a huge steel refinery named after Vladimir Lenin (the Lenin Steelworks) on the outskirts of Krakow, as well as an aluminum smelter on the other side. However, Schafer said the refineries’ chimneys didn’t have filters, and the industrial constructions were in stark contrast to the rest of the historic city.

‘The Sea of Suffering’ in Communist China

Poland became free from communist rule with the overthrow and collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989. Schafer believes the same fate will be faced by China’s communist regime today.“Just like with the persecution of Christians during the Roman Empire, the evil CCP will crumble for torturing to death millions of good innocent people,” she said.

“Many became orphans or lost family members they loved. A beautiful rainbow takes some of them to heaven,” Schafer said, referring to the children in her painting, whom she has depicted sitting on white lotus flowers—representing “purity and innocence”—reaching as far as the horizon.

Each child depicted in the painting is a real child with a true story of persecution.

In Schafer’s painting, baby Meng Hao is seen clutching a closed lotus flower, which represents his deceased mother. He’s also in the rainbow, which is taking him to heaven.

“Children suffer in silence,” Schafer said. “Often they are born into a suffering world, they accept it, because they don’t know anything else, but deep inside, the damage is horrendous.”

‘Buddha Light Shines in Hong Kong’

In another oil painting, titled “Buddha Light Shines in Hong Kong,” Schafer depicted a true-to-life event, of a father and his two daughters who'd recently traveled to Hong Kong from Australia to inspire and bring hope to people.“After returning to China, it became a nightmare for many,” Schafer said, referring to the 1997 handover of Hong Kong to the CCP and the citizens’ fight to retain independence from communist rule in recent years.

Hong Kong’s large bronze buddha statue on Lantau Island is depicted in the top corner of the painting, radiating divine light onto the scene. The words on the blue banner read, “truthfulness-compassion-forbearance,” the guiding principles of Falun Gong, said Schafer, who herself is a practitioner of the ancient cultivation way.

‘Purity and Good Nature’ of Children

Schafer, who believes “peace and good values will prevail,” hopes her paintings will spark curiosity in some viewers. She says that even if for a moment they ponder about the meaning of life, her work is not in vain.“I truly believe that the only way out for mankind is if people correct their own mistakes and improve their kindness and compassion for each other,” she said.

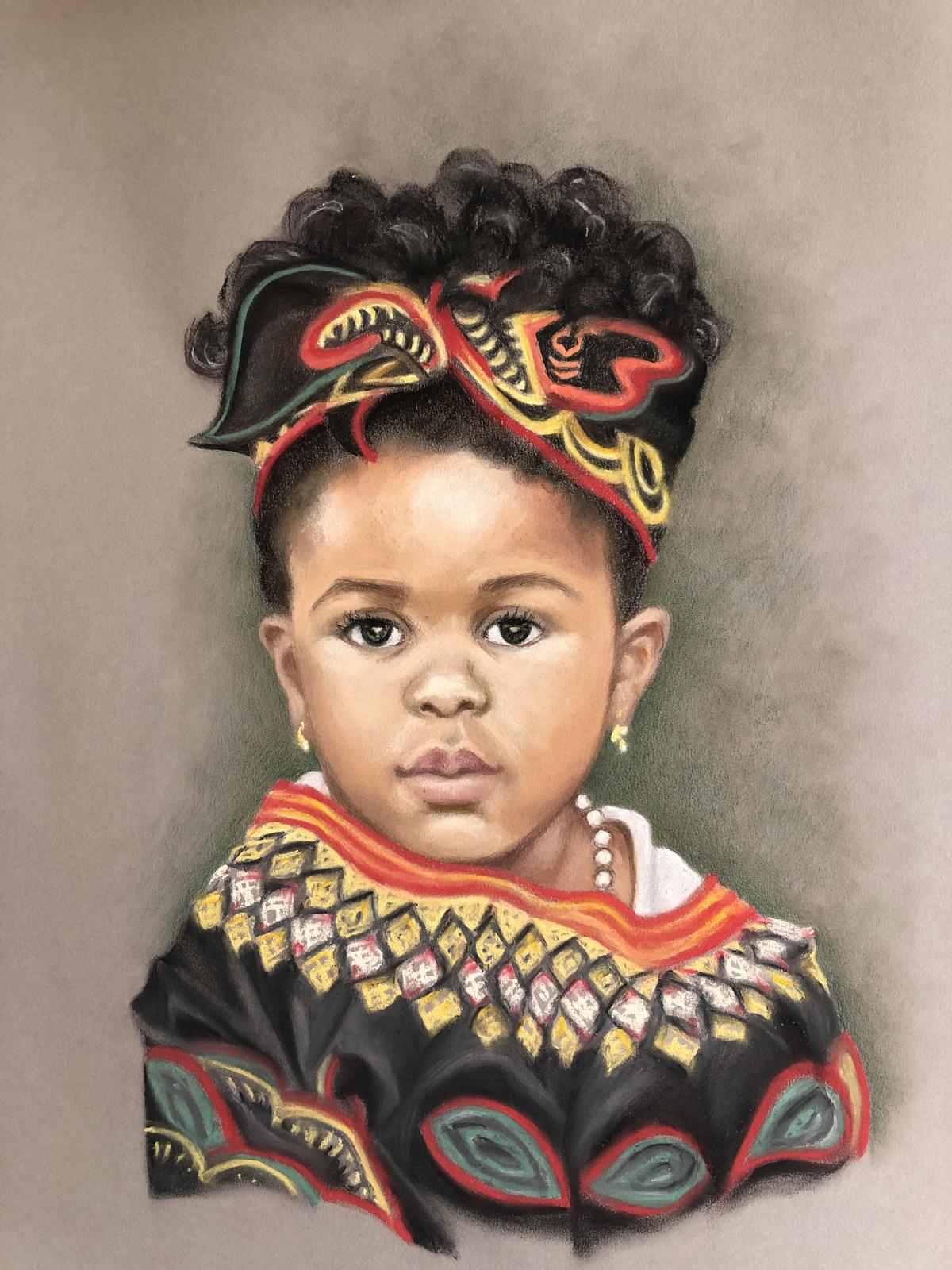

Schafer especially likes to depict the “purity and good nature” of children from different countries in her artworks. “They have so much in common before they grow up and become influenced by their society,” she said.

View Schafer’s Paintings of Children Below: