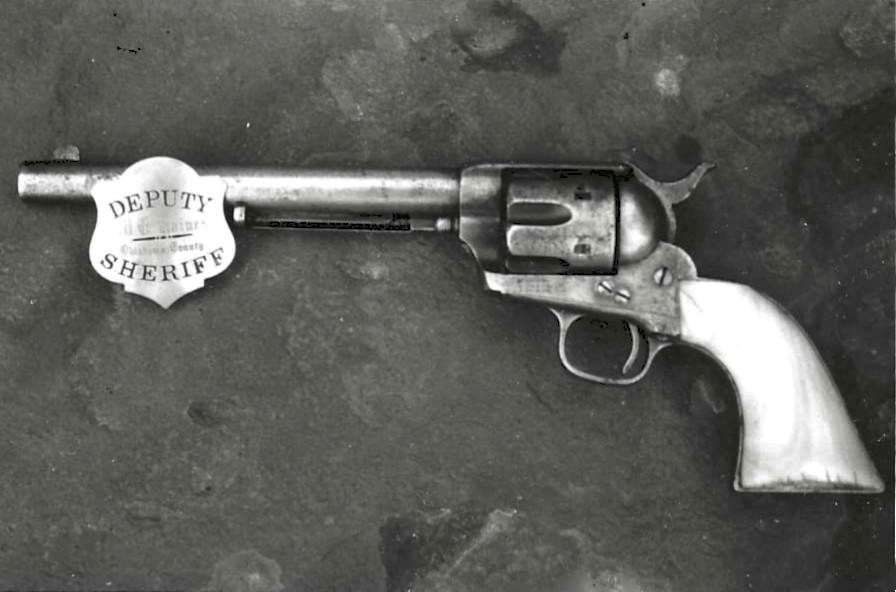

Even as a youngster growing up overseas, Oklahoma was always “home.” It was also the homeland of my childhood hero. I never had the privilege of meeting my hero, as he died in 1928, but my father told me amazing stories about my great-grandfather, U.S. Deputy Marshal Wiley G. Haines. As a result, I grew to know him very well.

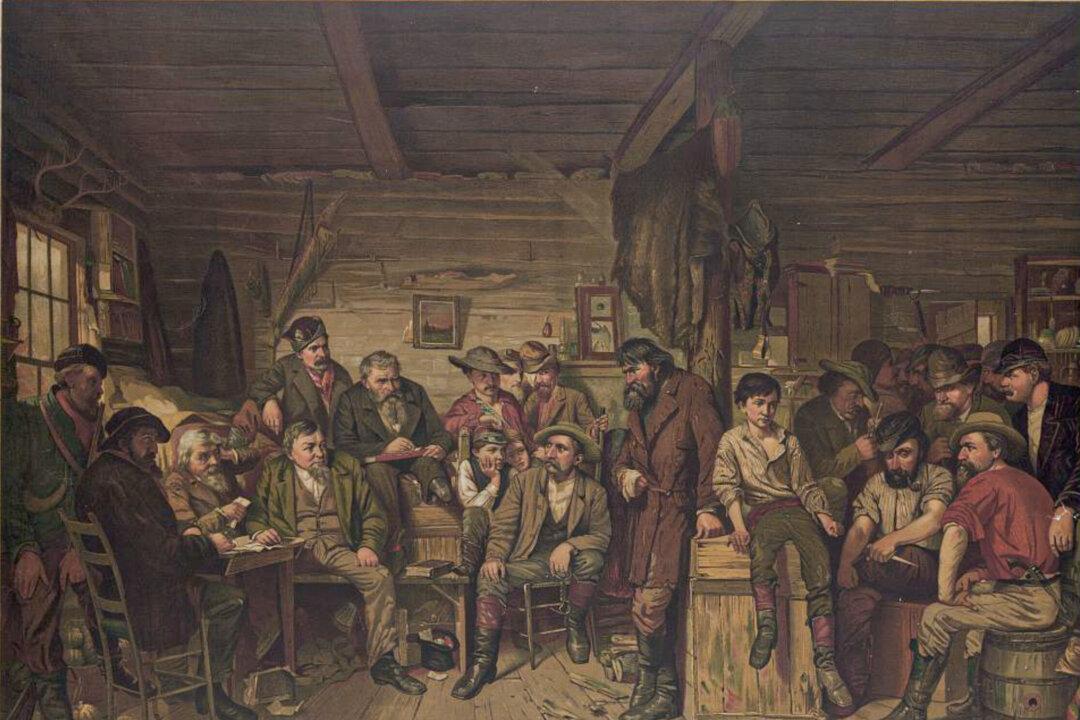

As a boy, I can remember sneaking out of bed past my bedtime to hide behind a chair and watch my favorite TV show, “Gunsmoke.” Marshal Matt Dillon was my TV hero, but in time I became much more impressed with the exploits of my real-life hero and great-grandfather.