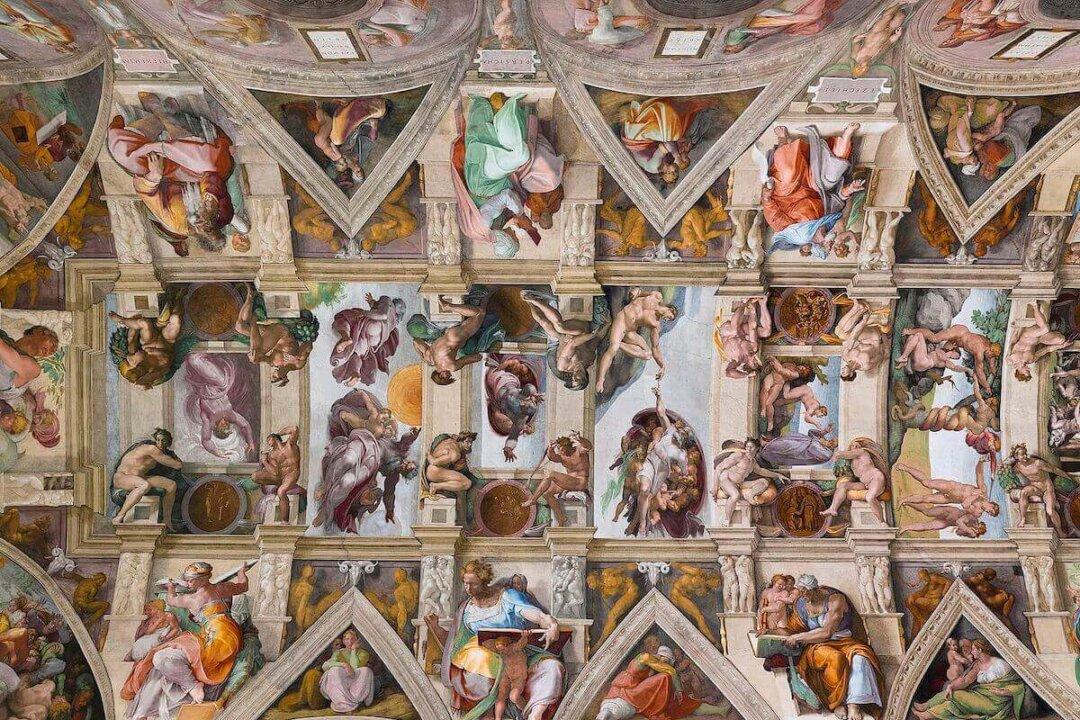

The musty smell of lime plaster fills the air just under the chapel’s ceiling. The artist works quickly on each section of the fresco as he stands on a scaffold platform 68 feet above the floor.

Along the perimeter of the high barrel vault of the Sistine Chapel, Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti paints 12 prophetic figures—seven male and five female. The artist depicts the figures as deep in thought, or reading, writing, and listening to God speaking to them.